Despite their continued underrepresentation in the fine arts, women have played a critical role in the history and the rise of the relatively young medium of photography. In celebration of Women’s History Month, Tia Collection turns our lens on some of the outstanding women photographers in the collection. From editorial and fashion photography to social documentary and conceptual, mixed-media work, the artists below capture the spirit of a continually evolving medium even while their place in it continues to be reevaluated and rightly championed.

Ruth Orkin had two passions in life: travel and photography. At the age of 17, Orkin completed a cross-country road trip by cycling and hitchhiking, all while snapping pictures along the way—a practice that would endure throughout her life of travel.

The photo above was conceived while on assignment in Europe for Cosmopolitan magazine. Orkin met Ninalee Craig (pictured) in Florence, and quickly bonded over their shared passion and experiences as women traveling solo. “The idea for this picture had been in my mind for years, ever since I had been old enough to go through the experience myself,” Orkin later wrote. “Here was the perfect setting I had been waiting for all these years….And here I was, camera in hand, with the ideal model! All those fellows were positioned perfectly, there was no distracting sun, the background was harmonious, and the intersection was not jammed with traffic, which allowed me to stand in the middle of it for a moment.” The photograph, with its eloquent blend of realism and theatricality, became the center image for her essay, “When You Travel Alone…,” which offered tips on “money, men and morals to see you through a gay trip and a safe one.”

Lillian Bassman entered the world of magazine editing and fashion photography as a protégé of Alexey Brodovitch, the renowned art director of Harper’s Bazaar. As co-art director of Junior Bazaar, their spin-off aimed at teenage girls, Bassman became widely celebrated for her artistic talent and begun frequenting the darkroom on her lunch hours to develop images by fashion photographer George Hoyningen-Huene. “I was interested in developing a method of printing on my own, even before I took photographs,” Bassman told B&W magazine in 1994. “I wanted everything soft edges and cropped.” She was interested, she said, in “creating a new kind of vision aside from what the camera saw.” Her access to several well known fashion photographers, including Richard Avedon who lent her his studio and assistant when away on shoots, allowed her to continue her self-education.

Bassman approached photography as a way to illustrate fashion, mapping her trained eye along the curves and flow of the body and turning blank paper into fashion plates. Her keen eye for what complements a woman’s body is evident in her black and white photographs of the most prominent models of her time, whose austere color belies Bassman’s penchant for fading, hazy lines, suggesting a dreamy, fluid atmosphere. Her work appeared frequently in Harper’s Bazaar, and she developed close relationships with a long list of the era’s top models, including Barbara Mullen (her muse and subject of this photograph), Dovima and Suzy Parker.

Sylvie Fleury moved from Geneva to New York City as an au pair after her initial schooling. During this time she began helping a group of NYU students make short films, eventually inspiring her to study photography at the Germain School of Photography in 1981. Later, she became the studio assistant to Richard Avedon (Bassman’s friend and mentor).

Since then, her artistic practice has expanded to sculpture, performance, installation and painting, frequently employing materials and processes associated with early Conceptualism, Pop Art and Minimalism. Through her keen eye, Fleury interprets readymade objects, such as cars, neons and iconic fashion items, in a new light, questioning our obsession with luxury commodities and brands, as well as the patterns of consumption they create. To Fleury, nothing is off limits as a source of inspiration and inquiry: “I don’t think of my work as appropriation. I see it more as customisation.”

Mumbai-based photographer Ketaki Sheth began taking pictures of her city in the late 1980s under the guidance of renowned photographer Raghubir Singh. Ketaki’s work maintains a strong focus on people within their everyday environment. In the mid 1990s, Ketaki began to shift her time between India and the UK in order to photograph the Patel twins, a lineage dating back to the 15th century with a genetic oddity of commonly-occuring twin births. This series would later be published in Sheth’s first monoprint, Twinspotting: Photographs of Patel Twins in Britain & India.

Sheth has also devoted several years to documenting the daily life of the inhabitants of Sidi villages across small areas of western India. The descendants of African slave-soldiers, traders and Muslim pilgrims who migrated to India in successive waves between the 9th and 16th centuries, the Sidi’s languages, cuisine and clothes are Indian but their cultural and religious norms carry African roots, seen in their musical instruments, dances and religious practice. Driving through the Gir Forest National Park while on holiday with her family, she caught a glimpse of a village enveloped deep within the forest. Her curiosity piqued, she spent the next six years learning about its people, and distilling imagery of beauty and grace from their day-to-day. Ketaki built a unique rapport with the close-knit community, resulting in a rich yet sensitive portfolio of square format, black-and-white documentary photography.

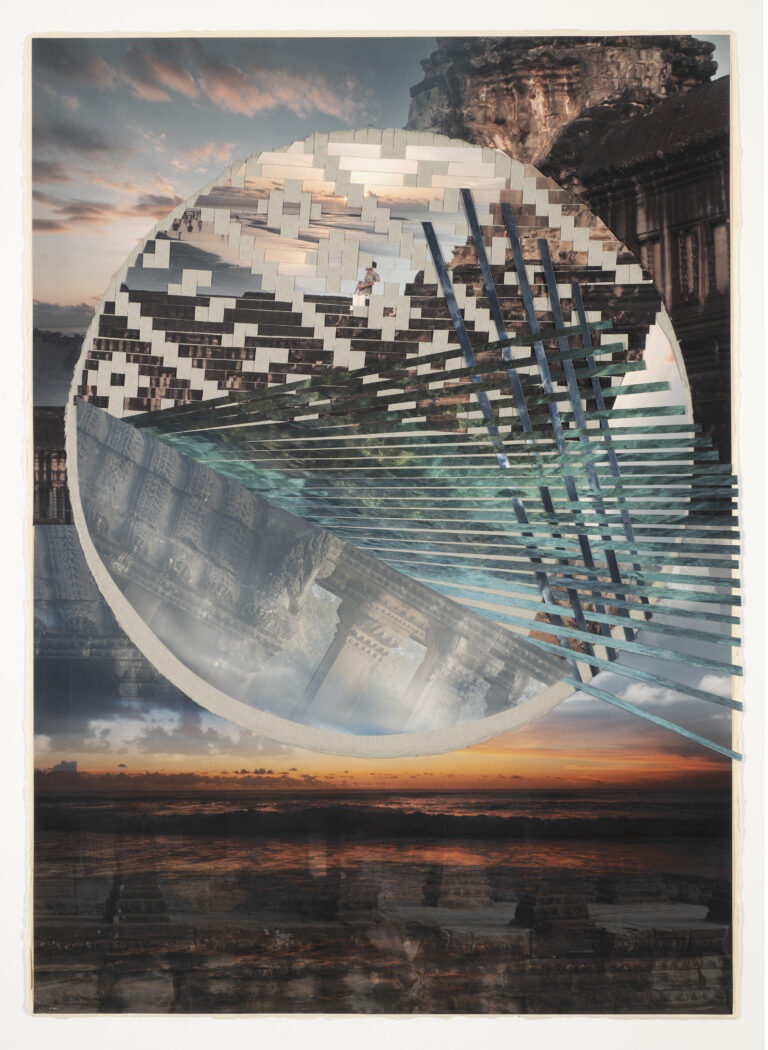

Sarah Sense’s unique style of photography is borne from her family tradition and her Louisiana tribal community. While growing up in California, Sense was deeply aware of the basketry of her Chitimacha relatives and her Choctaw grandmother’s extensive basket collection. At age 18, she began to research the Chitimacha basket collection at the Southwest Museum of the American Indian in Los Angeles at her tribal community’s request. With this knowledge, Sense returned to the Chitimacha Reservation with her sister to design activities for the youth during the summer months; during this time, she began to experiment with the concept of weaving photographs that she had taken of the reservation. Combining mylar, bamboo paper and other found objects and materials, Sense began to weave ancestral patterns like “raven’s eye” or “rabbit’s foot” in her pieces.

While Sense’s early works are based on Chitimacha landscape in Louisiana and Hollywood interpretations of Native North America, in 2013 Sense learned that her Chitimacha ancestors had been enslaved and taken from Louisiana to the Caribbean. Her series Weaving Water explored and reflected upon the use of water in terms of forced and voluntary migration, trade and subsistence. Sense writes of the series, “…despite the cluttered clash, people can return to a source to bring them back to the ground, returning them to a home that maybe can only be felt inside, because perhaps home has been removed.”

Artist Portraits (above left to right): Ruth Orkin, Lillian Bassman, Sylvie Fleury, Ketaki Sheth, Sarah Sense.