Tia Collection is pleased to announce Wild NM, organized in support of Vivarium: Exploring Intersections of Art, Storytelling, and the Resilience of the Living World at Albuquerque Museum. In Vivarium, named after the Latin term “place of life,” Albuquerque Museum Head Curator Josie Lopez, PhD invites viewers to consider the potency of art in fostering deep connection with the non-human living world. Wild NM, curated by Marissa Fassano, Project Manager at Tia Collection, highlights how artists express their deeply individual and personal histories, visual lexicons and interior and psychological lives through their friends in the animal and plant kingdoms. Through self-made fables and retold myths, and depictions of hopes and worlds both rich and devastating, the artists exhibited explore how they navigate their lives, communities and contemporaries through the lens of animism.

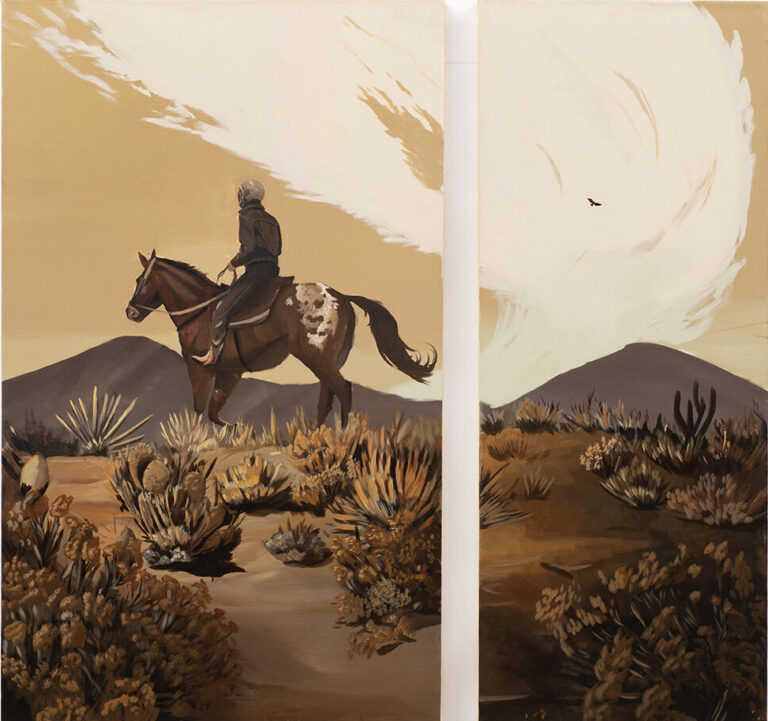

George Alexander (aka Ofuskie), b. 1990, Katy, TX, is a Muscogee Creek artist living in Santa Fe, NM. Alexander received his BFA from the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in 2016 and an MFA from the Studio Arts College International (SACI) in Florence in 2019. He was honored as a SITE Scholar (2015-2016)and received multiple awards from the American Indian Higher Education Consortium. In 2024, Alexander served as a First Peoples Fund Artist in Business Leadership Fellow.

“Ain’t From Around These Parts is a painting inspired by a vision that I have for humanity,” writes the artist. “This cosmic rider travels by horse in a southwestern landscape. They’re on a journey to find a place where they might belong and they are looking for purpose. One day I hope humanity finds a bigger purpose than just looking out for ourselves.”

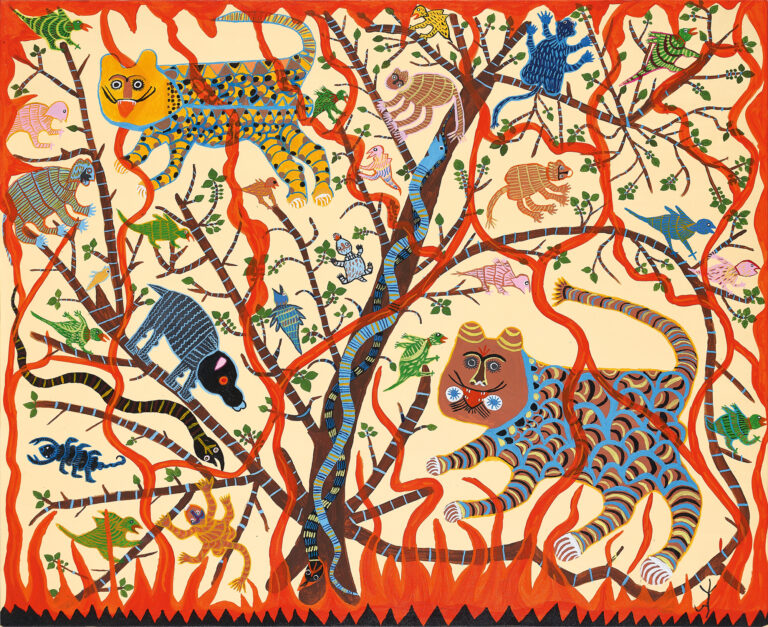

Jodhaiya Bai Baiga, b. circa 1939, India, is an Adivasi artist whose work is rooted in the forests that surround her village. The tiger Bageswar, or the tiger god that protects her community and their lands from wild boars and wolves, makes a frequent appearance in her paintings, as does the mahua tree.

This artwork is a response to the destruction of forests in Madhya Pradesh, India, where Jodhaiya lives. While the devastation is represented by brightly, flicking flames, Jodhaiya’s penchant for intricately patterned animals, which has been compared to the style and skill of legendary Gond artist Janghar Singh Shyam, is on full display against the pale, monochrome background. Its sister, The Burning of Bandhavgarh Forest, is currently on view in Albuquerque Museum’s Vivarium exhibition.

Jules de Balincourt, b. 1972, Paris, France, explores indoor and outdoor spaces in his paintings that suggest ever-changing landscapes—both physical and psychological. Often featuring a luxurious presence of nature, he conveys an imagined sense of time and place, reminding the viewer that we also inhabit inner worlds.

In this work, the artist explores private themes via an ambiguous island scene and figure. A stream of people with boxes and luggage are seen embarking or disembarking from one boat to another. Their bodies, sun-dappled under the shade of tall palm trees, are ensconced in not only the land mass and fauna, but also by an ominously floating profile. Climate crisis, refuge or simple getaway pleasure can all be read, but de Balincourt cloaks his private meaning, suggesting we do the same via our own instinctual, psychological response to this mysterious world.

Blake Debassige, 1956–2022, Ontario, Canada, was a M’Chigeeng Anishinabek (West Bay Ojibwe) artist who practiced the Woodlands School style, founded by Norval Morrisseau, which emphasizes outlines and X-ray views of people, animals, and plant life. While Ojibwe legends feature prominently in his pieces, Debassige also championed many pressing political issues through his artwork, such as environmental degradation and Indigenous language preservation.

The artist created this work in response to the 1985 formation of SCANA (Society of Canadian Artists of Native Ancestry). At the time, SCANA was led by Indigenous artists Bob Boyer, Carl Beam, Ron Noganosh, and Robert Houle—seen here as the four menacing dogs surrounding the center dog, who Debassige referred to as the “metaphorical woodland artist.” He is playfully raising a concern shared among more traditional “Woodland” Indigenous artists at the time, that SCANA was merely an extension of and working on behalf of the colonialist art establishment. According to the artist, SCANA’s sole reason for existing was to promote their more contemporary, international-looking approach to art-making, and thus discredit the approach of the Woodlands-school artists, many of whom originated from Manitoulin Island and incorporated more typically “Indigenous” symbolism in their work.

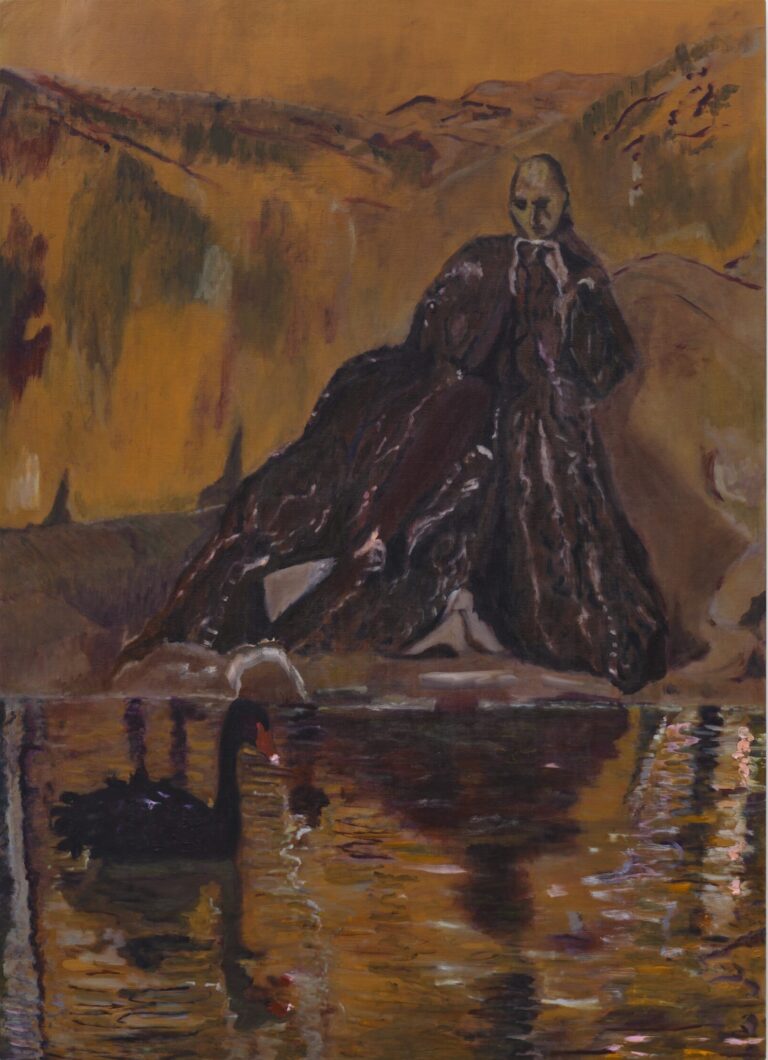

Helena Foster, b. 1988, Benin City, Nigeria, draws from personal experience to explore daily conflict and nostalgia. Often rephotographing material sourced from her own archive, Foster strips the scene to the intimate moments shared between two figures. The dream-like characters are concerned with psychological or spiritual states, sometimes indistinguishable from their surroundings.

Here, Foster depicts Tiresias—the mythological Greek prophet who was, according to various stories, punished for inflicting harm to a pair of mating snakes and later blinded—gazing at a swan on the waters. As balm for his blinding, he was given the gift of understanding birdsong, and thus prophecy. Foster pulls this particular scene from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1976 film Oedipus Rex. The artist’s interest in Greek mythology, Italian cinema and religion all converge in an offered shared experience of nostalgia and story, centered around the ever-rich fount of ideas and meanings that winged beings have stirred in humanity.

Retha Walden Gambaro, 1917–2013, Lenna, OK, was an artist of Este Mvskokvlke [Muscogee (Creek) Nation] descent whose favorite subject matters included animals and the family. In the early 1980s, her and her husband spearheaded the creation of the Amerindian Circle, an organization that sponsored one of the largest exhibits of contemporary Native American art at that time. Years later, Circle members from this organization encouraged the Smithsonian Institution to create a museum dedicated to the work of Indigenous artists in Washington, DC.

Animals were a favorite subject matter of Retha’s, who felt closely connected to nature from her childhood years working on a farm. She often portrayed them affectionately, and in relation to their family unit. “Animals have given me comfort and joy since I was about five years old,” she said. “I feel that we are all creatures of the same source. And that if I have what is called a soul, this little cat has one, too. And so do those little bunnies I see out in my woods.” In this work- part wall hanging, part soft sculpture, Retha builds a portrait of a weasel, common to Northeastern Oklahoma. Retha may have depicted the usually brown-coated weasel in his white winter coat, or this may be a kit, who are born with white coats.

Patrick Dean Hubbell, b. 1986, Mesa, AZ, Diné (Navajo) is inspired by the environment and the spirit of the natural world. His work exhibits an appreciation for the geometric designs of Navajo weaving and textiles, while exploring abstraction through the lens of modern art. Hubbell’s titles and concepts reference the matrilineal respect for Mother Nature, as the Diné people see her, and often references the Southwestern landscape, vegetation, and flora through his color.

This work appeared in the artist’s 2022 solo show Tack Room—exploring a deeply personal blend of Hubbell’s coming-of-age on his family’s Navajo Nation farmland and the difficulties he faces as a contemporary Indigenous artist. The show, which literally resembled a tack room, or a stable used to store riding and other ranching gear, was also clever installed, as Hubbell likened himself to the gallery’s “stable” of artists. Your Healing Touch is at once romantic—for its imagined care of the absent mare— but also rejected for its romanticism. The connection here—

Tetsumi Kudō, 1935–1990, Osaka, Japan, was shaped from an early age by the destruction of the Second World War. In a wide-ranging practice spanning four decades, he explored the effects of mass consumerism, technology, and ecological degradation through works that asked viewers to see themselves part of an intricate cosmos in which nature, technology and humanity influence each other in a system he dubbed the “New Ecology.”

Translated as “Freedom of the stallion,” this work from Kudō’s series of small pet cages encourages viewers to confront and put aside ego. Kudō’s micro-worlds cultivate an uncanny fusing of imagery derived from the artist’s highly personal visual lexicon that includes eyeballs, crawling penises, cacti, plastic flowers, pills, transistors and thermometers. His “visual maquettes” draw viewers into a world of mutations and self-organizing biological systems that reflect the desolation and decay mankind has wreaked upon the macroscopic world.

Kiki Smith, b. 1955, Nuremberg, Germany, incorporates animals, domestic objects and narrative tropes from classical mythology, folk tales and religion to address the philosophical, social and spiritual aspects of human nature and identity, and the complex, symbolic relationships between humans and animals. In 2005, Smith was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters and in 2016, the International Sculpture Center awarded her their Lifetime Achievement Award.

In the early 1990s, the natural world—and the animal kingdom in particular—began to appear in Kiki Smith’s work. Smith made her first sculpture incorporating a bird in 1992, and since then, birds have remained a powerful symbol throughout her practice, evoking associations with the Holy Spirit (Smith was raised Catholic) and her identity as a woman and feminist. Smith frequently visits the Carnegie Museum of Natural History to look at taxidermied bird specimens, and often portrays her rendered animals as self-portraits. The gilded couple of Back Porch Whispering, seen with wings spread and touching beaks as if offering a kiss amongst the storm of chaotic bars surrounding them, represents the artist and her husband.

Sophie von Hellermann, b. 1975, Munich, Germany, creates romantic, almost weightless paintings by applying pure pigment directly onto unprimed canvas. Her subjects recall the look of fables and legends and are imbued with the workings of her subconscious rather than the content of existing images. Von Hellermann received her BFA from Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf and an MFA from Royal College of Art, London.

Von Hellermann exalts her home base in this tremendous yet featherlight canvas from a series of paintings inspired by Dreamland, an iconic funfair and “pleasure garden” set within the coastal resort of Margate, UK, where the artist lives and works. In Mid Flight, an excellent example of the artist’s signature swirls and seemingly weightless compositions, a soaring bird hovers above Dreamland’s thrill-seekers, as if the artist herself has flown above for the bird’s eye view of the grounds, or as if a rider below has sprouted wings from the sheer swelling joy at the fair.

Special thanks to William T. Gassaway, PhD and Josie William, PhD of Albuquerque Museum.

Written and designed by Sarah Greenwood.