In the third installation of Tia x Chatter, we are proud to present I Say With My Full Essence, an exhibition celebrating the work of eight contemporary women artists who draw from powerful and personal reserves to grow and shape not only their practice, but our understanding of women in the arts sphere. Included too in this celebration are the women who support the arts—the arts administrators, curators, cataloguers and fans—as each work is accompanied by words from the women of Tia Collection. Read on to learn more about what inspired each Tia team member’s chosen artwork.

As a self-described hoarder, Mandy El-Sayegh, b.1985, incorporates personal memorabilia into her work, overlapping latex and fleshy-hued paper from old copies of the Financial Times along with her father’s calligraphy. By doing so, she is creating a visually rich and dense aesthetic while positioning the body—and herself—at the center of the work. These seemingly disparate materials, or “fragments,” are brought together in a process the artist says is “like surgery,” referring to her collage process as “suturing” and her painted surfaces as “skins.”

In her ongoing series Net-Grid, she again alludes to the body by using a format reminiscent of a tailor’s or seamstress’ grid to organize and structure her compositions of a 1 cm squared red line on paper used to cut parts for garments. Here, the grid pattern insinuates the appearance of a medical mesh or gauze bandage for a wound.

– Sarah Greenwood.

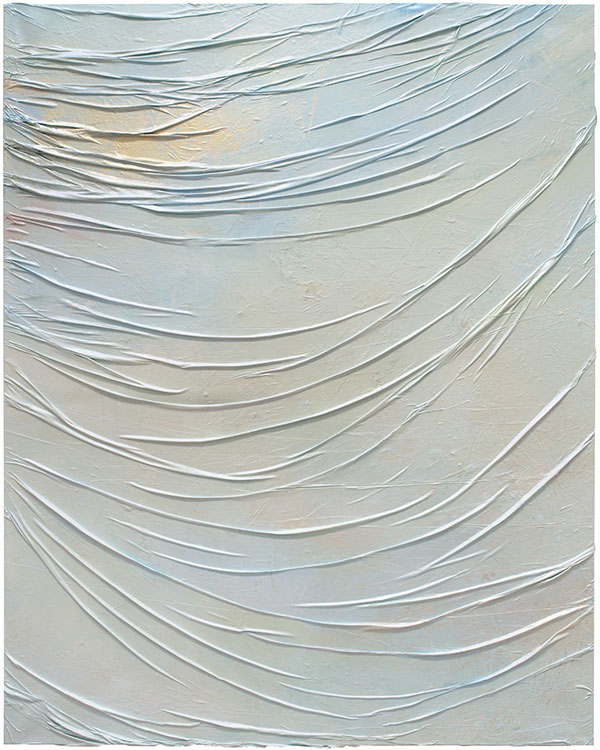

Marianna Uutinen, b.1961 has described her work as creating a performative space for people to project onto, which I think is a perfect fit for Tia’s collaboration with Chatter. From the Series “PlasticSky” 2 was made by using her signature technique—building up layers and layers of acrylic paint to make a skin, and then draping these skins directly onto the canvas. The process is reminiscent of both a child’s playfulness in building a fort or sandcastle, and also a performer’s facilitation of openness to express themselves, and the body, in various contexts.

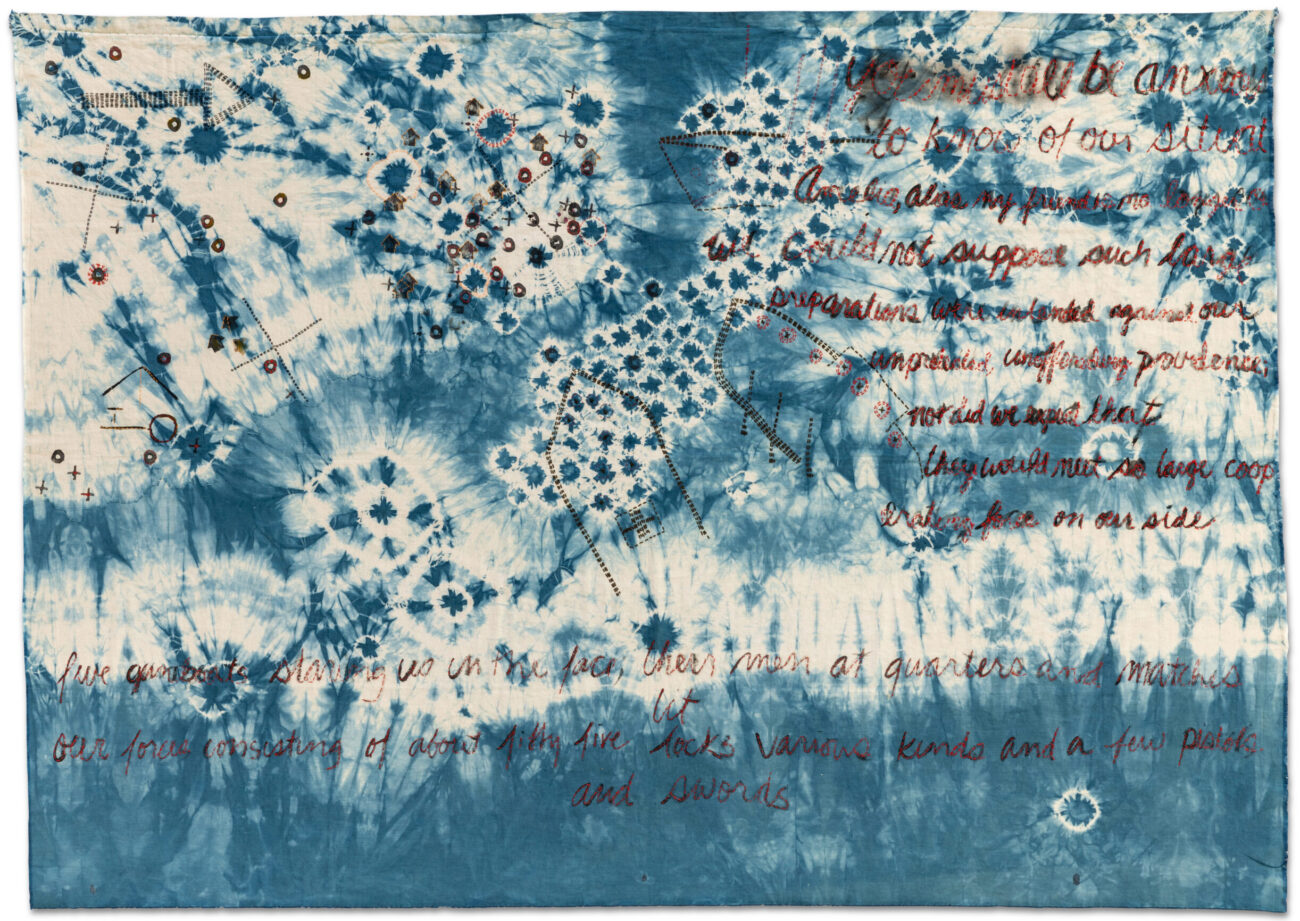

“This is sadness,” says Karen Hampton, b.1958. She’s referring to the story of Fernandina, Florida, a prospering city under Spanish rule where people of all races were flourishing and inter-marrying before the gunboats of Georgia and the Carolinas arrived to annex the city in 1813. The “Patriots” undid years of city planning and plotting, which Hampton, who refers to herself as a griot or storyteller, reflects in her bright red thread, outlining the gunboats amongst the watery swirls of her indigo-dyed fabric. Here, the elegant cursive, plucked from her ancestor’s hastily written note of the city’s loss, belies the generational destruction that occurred for land and ownership (in more ways than one, as the city was positioned well for slave-trafficking). Here, Hampton has pulled the Minotaur’s red yarn to unravel personal history and historical drama, conquering travesty in the spirit of reclamation and beauty, and commingling memory and hope through her capable hands.

– Marissa Fassano.

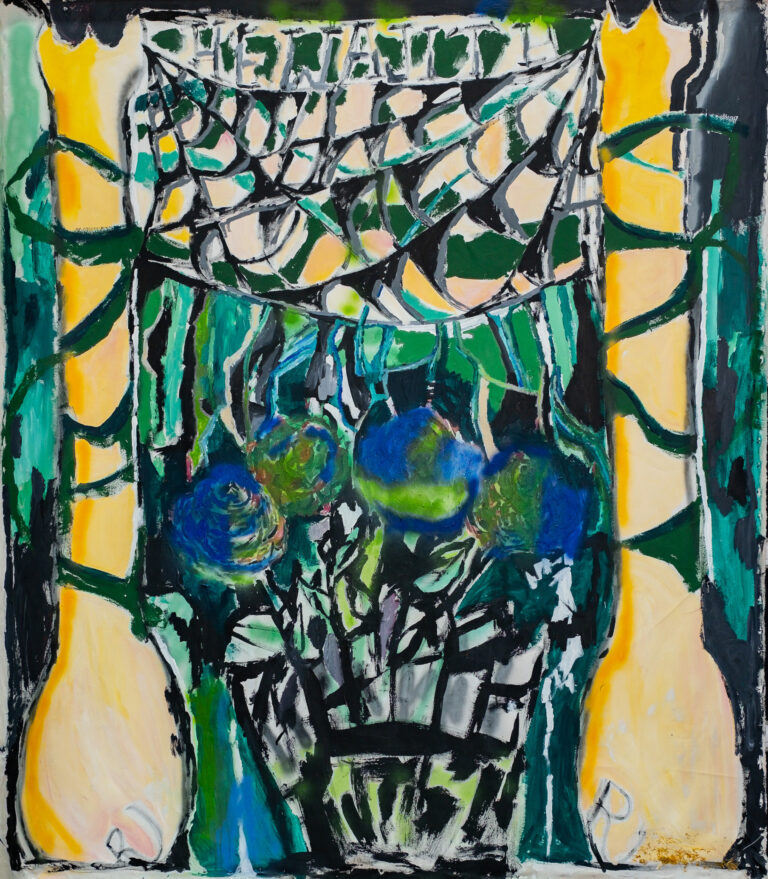

This exhibition derives its name from the eponymous artwork of Grace Rosario Perkins, Akimel O’odham (Pima), Diné (Navajo), b.1986. In the artist’s painting, blossoms and verdant leaves emerge from the canvas, blooming at its center, amidst a network of dark webs. These webs, simultaneously evoking notions of connectivity and entrapment, drape from above, framing the composition. Throughout the piece, indecipherable text weaves its way, a recurring motif in Perkins’ practice. Like thoughts drifting through the mind or the rhythmic lyrics of a song, these words linger. A storm of words, webs, and blossoms are flanked and framed by two large beams, as if supporting the painting itself, holding upright strong against outside forces. Perkins’ artistic vision, rooted in her queer and Indigenous identity, celebrates the emotive power of paint and collage, embracing a stream-of-consciousness approach where every inch of the canvas is considered.

– Brooke Denton.

Max Cole, b.1937, is best recognized for her category-defying fine line paintings. Her work is seemingly simple and monochromatic and yet, as one moves more closely to look at the painting, it unveils itself to the viewer. The fine lines cross the expanse of the painting in a vertical or horizontal orientation, juxtaposed against layers of paint or raw linen, lead to a deeper appreciation of her meditative world.

The fact that all of the lines are hand drawn are evident. Her marks are a passage of time. She literally leaves everything she experiences while making each work on the canvas itself.

Max has further brought a new visual language to both of these works by evoking the feeling of moire silk, creating a watering feeling to each work, and fooling the eye. At 87 years old, Max is still pushing boundaries, exploring all she knows and challenging the viewer to continue the journey with her.

– Laura Finlay Smith.

Within the minimalist framework of Sarah Rapson, b. 1959, a small black-and-white photo, carefully affixed to the panel, serves as a focal point. It evokes a dual sensation: the coldness of contemplation and the warmth of cherished memories. This deliberate use of minimal imagery allows the viewer to create their own narrative surrounding these lone, stoic and boldly quiet panels. Rapson’s art explores the depths of presence within emptiness.

– Brooke Denton.

Rapson may be an artist’s artist—her stream-of-conscious, off-the-cuff show statements and art historical game of darts is a pleasure for any committed investigator—but she’s also clearly a girl’s girl, even if we think she might also be an “it” girl. Collaged art world papers and photos in her at turns funny, punky or ironic hands are a window into her world. Is it obscure, blurred? Maybe—but it’s hers, and therefore, essential. And what you see—how can that also not be essential, in this world of poetry and song and art whose curtain Rapson lifts, with a wink?

– Marissa Fassano.

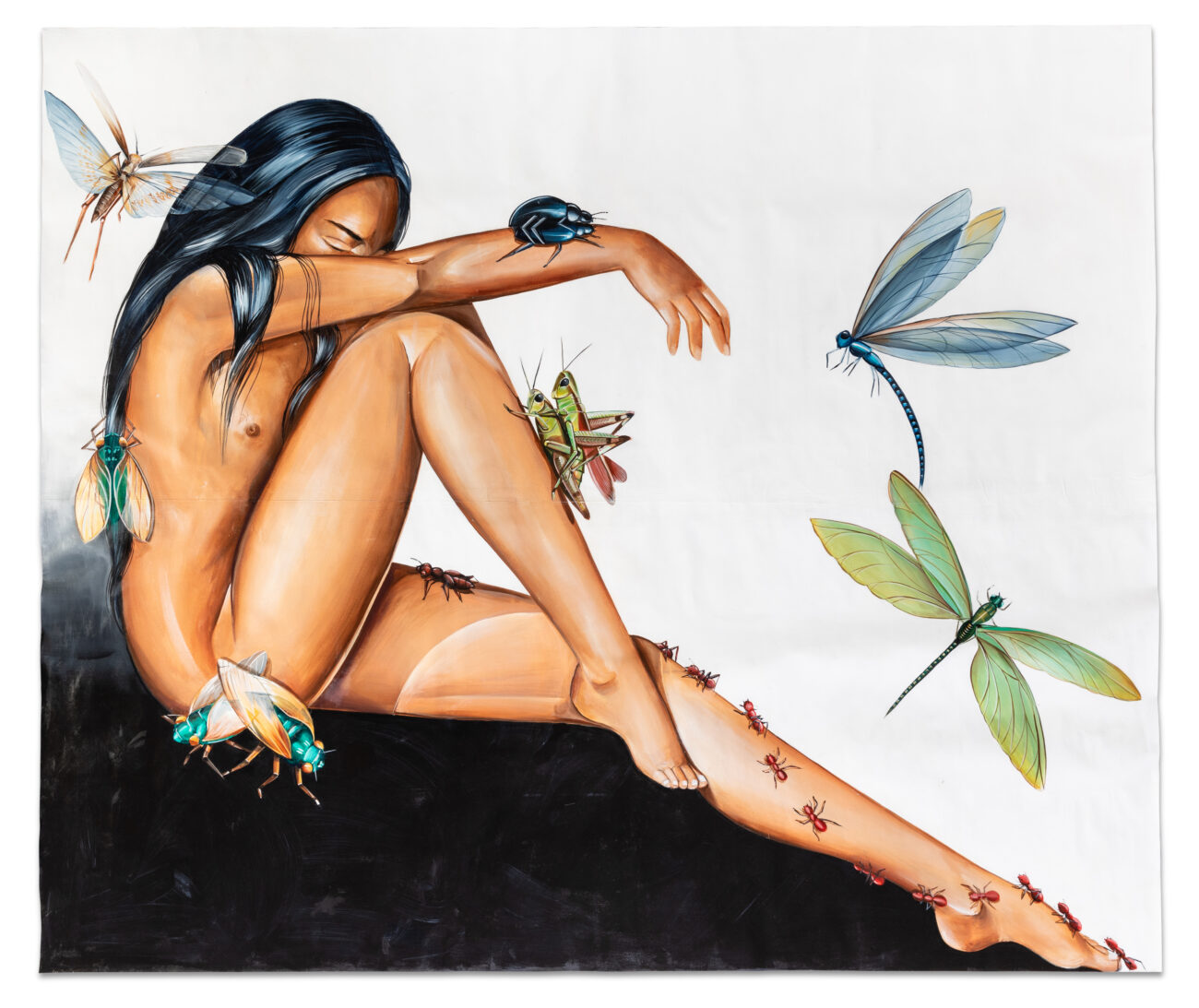

What better way to anchor a show around the personal histories of women than the larger-than-life, universe-stradding work Between Two Worlds by Nanibah Chacon, Diné (Navajo), Chicana, b.1980. Through Nani’s signature medium and scale, this gender-neutral figure recalls the transition between the first and second worlds in Diné mythology. “The first humans brought into the second world were the first, second, third and fourth genders,” writes the artist. “This piece acknowledges the precipice of change and the uncertainty of transition when moving from one thought into another.” Standing before the monumental body, we cannot help but acknowledge our own transitory states, as well our ever-changing, ever-growing place within our community.

– Marissa Fassano.

This cunningly titled piece by Dorothy Cross, b.1959, takes one back to the roots of humanity and religion invoking the themes of “mother” and “woman.” Originally created as a part of the International Biennial of Public Art: Edge in 1992, the work consists of 12 handblown glass chalices, coated in a thin layer of liquid silver and each with a unique form.

Every aspect of the piece solicits a deeper meaning. The title unmistakably references Da Vinci’s The Last Supper, but in Cross’ case, her twelve objects transcend the twelve apostles. Each piece suggests a gendered form either that of phallus or breast, touching on the cursory duality of male/female and body/blood. However, they also provoke the more profound symbolism that the breast or teat, as described by Cross, nourishes life, an innately motherly attribute and belongs to females, whom bleed to create life. This powerful metaphor struck me as the artist’s utter rejection of the patriarchal foundation of Christianity. The First Supper’s inclusion of “woman” in its creation demonstrates Cross’ ability to challenge the viewer beyond learned understanding.

– Emma Smith.

I Say With My Full Essence also marks the inauguration of the Tia x Chatter Mural Project with a 34-foot mural by Heidi Brandow, Diné (Navajo), Kanaka Māoli (Native Hawaiian). While the exhibition was initially inspired by March’s observance of women, present and historical, we acknowledge the importance of exhibiting and supporting women artists to balance predominantly male-saturated spaces. Our unveiling of the Tia x Chatter Mural Project, followed later this year by Eliza Naranjo Morse, Kha’p’o Owingeh (Pueblo of Santa Clara), takes the concept of a women’s show well beyond a single gesture, and is a step towards creating a space where women’s voices are celebrated throughout the year.

In This Land / This Body, the New Mexico-based artist was driven to share the story of her native home’s ongoing displacement:

“Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) teachings emphasize the profound connection between the ‘āina (land) and our bodies,” writes Heidi Brandow. “Since the arrival of Europeans in 1778, Native Hawaiian populations have endured significant losses, with over 90% of their people perishing due to foreign diseases within the first year of contact, totaling upwards of 300,000 lives. Subsequently, Native Hawaiians have faced ongoing challenges, including continual displacement and disproportionately high rates of negative health impacts, leading to increased mortality rates. Additionally, there has been a disproportionate loss of land over time, driving many to leave Hawai’i. Presently, more than 60% of Native Hawaiians reside outside of Hawai’i, exemplified by the fact that there are more Native Hawaiians living in Las Vegas, Nevada, than on the island of Maui.

As Hawai’i experiences rapid growth and development driven by US and foreign investments, the native flora and fauna are dwindling due to habitat destruction and human encroachment, resulting in the extinction of many endemic species. For Kānaka Maoli living in diaspora, returning home to Hawai’i is a cherished privilege, yet it evokes mixed emotions as it underscores the ongoing displacement of our people and the transformation of once-Kanaka spaces into tourist destinations where we are marginalized and even charged to access our own cultural sites and lands. This mural serves as a poignant reminder of this reality, portraying endangered plants and animals that symbolize the struggles of Kānaka Maoli both in Hawai’i and abroad.

Ultimately, it prompts us to question: What is Hawai’i without Hawaiians? Collectively, we (Kānaka Maoli) yearn for our ʻāina hānau (homeland) and for one another.”

Later this month at the Muñoz Waxman Gallery: Join Nanibah Chacon on Saturday, April 13 at 12pm to learn more about Between Two Worlds, and hear from Charlotte Jackson Fine Art owner and director, Charlotte Jackson on Friday, April 19 at 5pm as she gives viewers insight into Max Cole’s practice.

Installation photography of Brad Trone.

Designed by Sarah Greenwood.