Since its founding in 2007, the collection has remained closely involved with the art and culture of South Asia. A painting by the Indian artist Maqbool Fida Husain was one of the first art acquisitions made by the founder. While the collection retains a core focus on the Modern artists of Post-Independence India, it has developed over time to explore both ancient South Asian artistic traditions, and the increasingly powerful voices of a vibrant contemporary Asian art scene.

Rob Dean has been involved with the collection since Tia’s inception and has assisted with the acquisition of art in various fields, but particularly South Asia. Highlights from this region include Modernist paintings by V. S. Gaitonde, F. N. Souza, S. H. Raza, and Akbar Padamsee, plus contemporary works by artists such as Rasheed Araeen and Atul Dodiya. The collection has evolved to encompass paintings and sculptures from the classical traditions of the region. – Laura Finlay Smith, American and Western Art Curator.

In Rob’s own words: I have been fortunate enough to have been involved with the arts of Asia for my entire career. I studied comparative religion at university and later the arts of Asia, but my focus has always been India. I travelled widely as a student and fell in love with the country, its art, and its multilayered cultures and peoples. It has been both a privilege and an artistic adventure to assist in building a South Asian section for the Tia Collection.

The challenge when asked to offer advice on what might constitute a valid addition to the South Asian collection is that the parameters are so vast. The Indus Valley civilization began over 5,000 years ago and artistic production has been present from the earliest moments of its existence to the present day. Currently India alone is home to over 1.4 billion people speaking more than 440 languages. The various artistic expressions that have evolved over such a time frame, and amongst such cultural and religious diversity is mind-boggling. Naturally, art collecting can only scratch the surface of the artistic potential of such a huge region and so rather than focusing on the more predictable ‘highlights’ of the South Asian Modern collection I have chosen a few works that I feel hint at the region’s artistic diversity and long history.

As the birthplace of four of the world’s major religions, it is unsurprising that for most of its history, the art of India is closely related to religious belief and ritual. The collection includes many such examples of religious expression, which were used as part of complex ritual practices, that reflect the profoundly spiritual nature of the communities who inhabited South Asia at various moments in its history. I have highlighted two examples, one Hindu and the other Buddhist.

The first example from the Hindu tradition is a 10th century black stone carving from the Kashmir region of Northern India. It depicts the god Shiva and his wife Parvarti surrounded by their family. Shiva is depicted seated on his bull Nandi, his left arm embracing Parvati. They are adorned with heavy beaded jewelry, and crowned with foliate diadems, each head encircled by a beaded nimbus. Flanking the central deities are their two sons Ganesha and Kumara who stand in attendance, Ganesha’s trunk curling towards a tempting bowl of sweets that he holds in his raised left hand. Only a few comparable compositions are known to exist, including a related composition of Uma-Maheshvara in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (M.78.103) and another version of the Holy Family which now forms part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1989.362).

Positioned at a cultural and geographical crossroads, sculptures from the Buddhist and Hindu traditions in this region display their own unique style, characterised by muscular bodies, serene faces with distinct almond-shaped eyes, and intricately detailed garments and jewelry. It is rare for compositions carved in this soft black stone to have survived intact from this period, and although intimate in scale, the current stone example retains a monumentality of form, with remarkably refined detailing.

The second example comes from the Buddhist tradition. Perry Rathbone, a former director of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, once said of Nasli Heeramaneck (prominate dealer and former collector of this work) that ‘his avocation was his vocation; he lived for art; it was his work and his play… An early accident left him with only one eye unimpaired, but as Cézanne said of Monet, “What an eye!‘’ It was therefore a great thrill to help the collection source this monumental gilt bronze Buddha, a superlative example of Tibetan sculpture from one of the most revered private collections of classical Himalayan art.

This iconographic form of Sakyamuni Buddha, in which the historical Buddha is presented in the earth-touching gesture (bhumisparsamudra) is one of the most universally recognised forms of religious sculpture from any religion. The calm seated posture recalls an episode from his spiritual biography in which he triumphs over Mara (maravijaya) just prior to his enlightenment. Poised on the threshold of enlightenment, Sakyamuni moves his right hand from the meditation position in his lap and touches the ground, calling the earth to witness. An interesting feature of this exquisite bronze is the jeweled diadem adorning the Buddha which may appear at odds with the austerity normally associated with Sakyamuni’s ascetic nature. However, in this case, the crown represents the Buddha’s triumphal detachment from the mundane world, and it is sometimes thought to be symbolic of the ancient Indian concept of cakravartin, the ideal universal ruler.

The tradition of adorning Buddha with a regal crown originated in India but was later enthusiastically embraced and adopted by the Tibetans through their espousal of the Buddhist teachings and artistic traditions found in Bihar and Bengal, in the 11th and 12th centuries of the Pala period. The sensuous modelling, elegant proportions and the spirituality expressed in the meditative countenance of the Buddha exhibits close ties with Nepalese sculptural traditions of a similar period, and suggests that itinerant Newar artists (who were from Nepal) are likely to have created this masterpiece of Himalayan art for their Tibetan patrons. Both of these early sculptures are testament to the supreme skills of the master craftsmen who created them and reveal a story of cross-cultural exchanges that occurred throughout the medieval period.

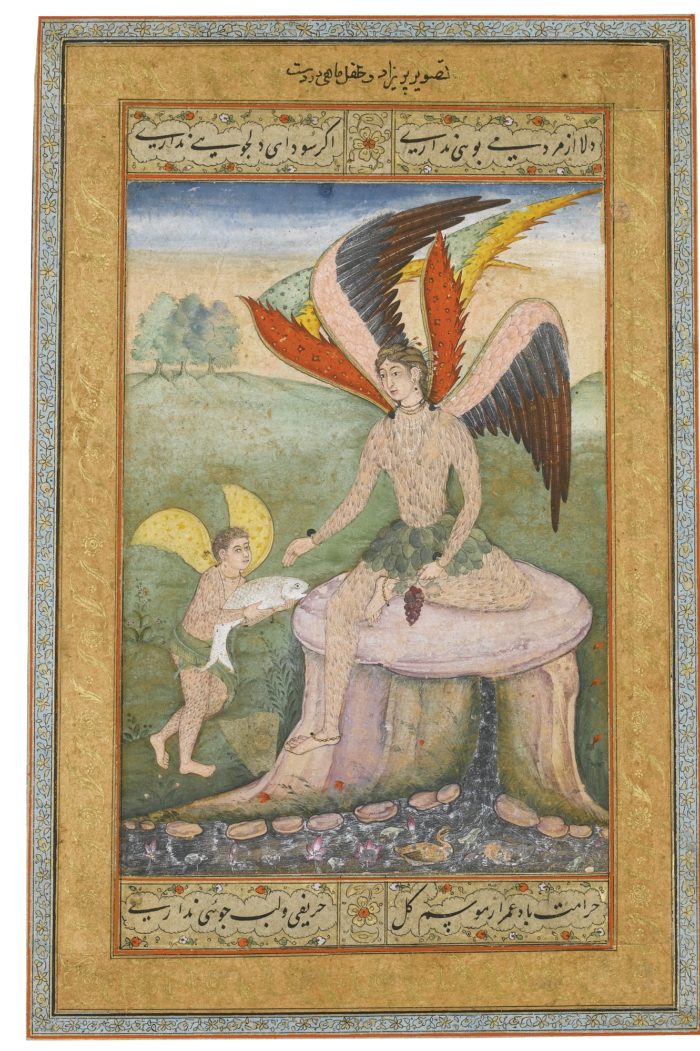

A further example of such cross-cultural exchanges comes in the form of a painting dated c. 1590, from the Mughal court of the Emperor Akbar the Great. The painting, attributed to the Mughal artist Manohar, depicts a version of the Biblical story of Tobias and the Angel. Like many artists working in the Mughal atelier, Manohar has chosen to adopt Biblical imagery, but has adapted it to suit his own artistic concerns. It is interesting to note that the artist has chosen to depict the angel Raphael as a female, and the young Tobias with wings, both elements which do not follow the religious text. Clearly multiple sources are at play in this one image, and it reveals a fascinating combination of European iconography from prints of Greco-Roman subjects, and Biblical illustrations, that were all circulating at the Mughal court by the late 16th-century.

The child-like figure with wings is probably inspired by Renaissance versions of Cupid who was frequently depicted at the feet of Venus, which may in part explain why the central angel has in this version become a female figure. Other elements of the composition may be drawn from Persian literary sources such as the Fables of Bidpai, or the Shahnama of Firdausi, while elements such as the leaf skirt, worn by the central figure, draw from other Mughal depictions of the local Bhil people, who were employed at the Mughal court as hunters. The painting is thus a fascinating blend of European, Indian and Persian sources that reflects the rich diversity of late 16th-century Mughal art.

A second example of a painting based on a Biblical theme is by the Indian modernist Francis Newton Souza. As his name suggests, Souza was a Roman Catholic of Goan origin and many of his most enduring images bear the influence of his upbringing. The artist explains, ‘as a child I was fascinated by the grandeur of the Church and by the stories of tortured saints that my grandmother used to tell me. As far as I can recollect, strange fancies always occupied my mind… On retrospection, today, it seems funny, almost ludicrous. But it created the artist in me.’ ( F.N. Souza, A Fragment of Autobiography, Words & Lines, London, 1959, p. 9.)

Souza had a complicated relationship with the Church, but Christian imagery held a fascination for him and became a key part of his own artistic vocabulary. He depicted Christ and other religious themes in a great number of works, but his contradictory feelings about Christianity are best represented in a series of large-scale canvases (which included the current work) that were painted in the early 1960s and exhibited at The Human and the Divine Predicament exhibition held at Grosvenor Gallery in 1964.

In The Deposition, Souza adopts his composition from Titian’s Entombment of Christ. In both works, the entire structure of the painting concentrates our attention on the monumental figures grouped around Christ, but unlike Titian’s painting there is no twilight glow to the saintly figures; instead, we are confronted by cold tones, desolate spaces and monstrous forms. The anguish of Christ’s torture on the cross is depicted in harsh reality for all to see. The scene a commentary on the brutal nature of mankind, rather than reverence to a loving God. This aggressive and bold style won him accolades amongst his critics in London, who compared him to his British contemporaries Graham Sutherland and Francis Bacon. The best of Souza’s works derive much from Western Art yet they are never derivative. Many elements of his paintings are inspired by a deep understanding of Indian artistic traditions, but, as John Berger famously stated Souza ‘straddles several traditions but serves none.’

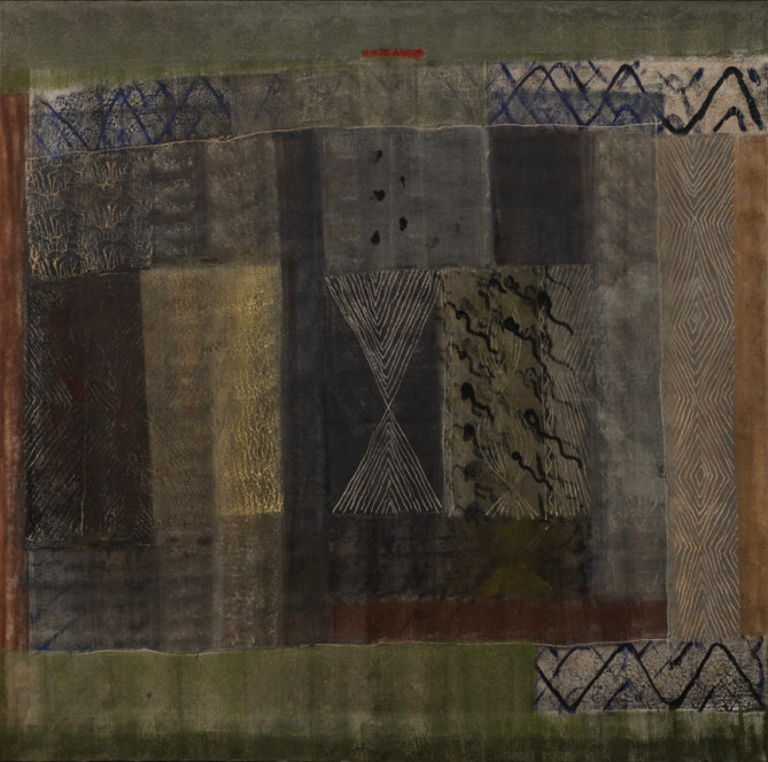

The final work highlighted is an untitled abstract painting by Jagdish Swaminathan from 1993. It is a work from what critics later termed his Tribal period. Rejecting western modernist movements, he became a founding member of Group 1890, whose manifesto stated, “… creative expression is not the search for, but the unfettered unfolding of personality. A work of art is neither representational nor abstract, figurative or non-figurative, it is unique and sufficient unto itself, palpable in its reality and generating its own life.” (Group 1890 Manifesto, New Delhi, July 19, 1963, reprinted in Lalit Kala Contemporary 40, New Delhi, March 1995, p. 84)

The Group’s manifesto became central to the manner in which Swaminathan approached his own practice. He felt that the future of Indian art had to consider the traditional Indian approach to art which was never meant to represent reality, but rather, it should aim to be a “poetic rendering of ideal truth.” As such, his career can be seen as multiple manifestations of this basic principle, beginning with the Colour of Geometry phase, followed by the Bird, Tree and Mountain period, and finally the Tribal period. At the end of the 1980s, Swaminathan’s works underwent a dramatic change in subject as well as technique. He moved away from the more formal explorations of colour and scale that had occupied him for the previous decade, and returned to his original point of interest: tribal motifs and folk art. Writing in the same year as the current work, the artist states, “Madhya Pradesh brought about a basic shift in my painting again. The live and vibrant contact with tribal cultures triggered off my natural bent for the primeval, and I started on a new phase recalling my work of the early sixties.” (Jagdish Swaminathan, The Cygan – An Auto-bio note, op. cit., p. 13)

Visually, the works return to the imagery of the 1960s with calligraphic forms, geometric shapes and texture playing an important role. Some of the elements draw inspiration from specific folk symbols and legends; others are entirely of Swaminathan’s own creation. Geometric shapes, especially triangles and squares reappear and take on evocative significance. The overall effect in this later work is an energised picture plane, vibrating with movement and vigour. In these later works, we are witness to the distant echoes of the earliest moments of Indian artistic activity, for one can perceive in them the influence of a continuously vibrant living tradition of Indigenous art that draws its own inspiration and nourishment from the deepest and most primordial roots of Indian art and culture. In essence we have turned full circle, returning once more to the earliest ritual markings on the cave walls of prehistoric man.

This cyclical sense of time, or perhaps more accurately a non-chronological approach to art history, is often key to a better understanding of artists and artwork that fall outside of the mainstream western art historical dialogue. For me, it is exciting to see that Tia Collection, through its range of artists and cultures, does precisely that. The recent addition of some works by key Indigenous artists from India is one case in point. It challenges the accepted norms of what one should consider “important.” By placing the work of non-metropolitan artists alongside the famous names of the 20th century, the artists are presented as equals in a contemporary dialogue. Certainly, it is a project that Swaminathan would have applauded and an artistic journey that I am excited to witness.