Tia Collection is fortunate to have acquired several works by Marie Watt (Seneca, Scottish, German), whose Native American heritage is at the forefront of inspiration for her mixed media works. Repurposed blankets are the basis for much of her work and embrace the fact that they have been well loved by their owners and then passed down for generations before reaching the artistic purpose conceived by Watt. They allow her to conceptualize a truly unique form of storytelling which expresses mythology, history and activism. She is a conduit for the past into the present.

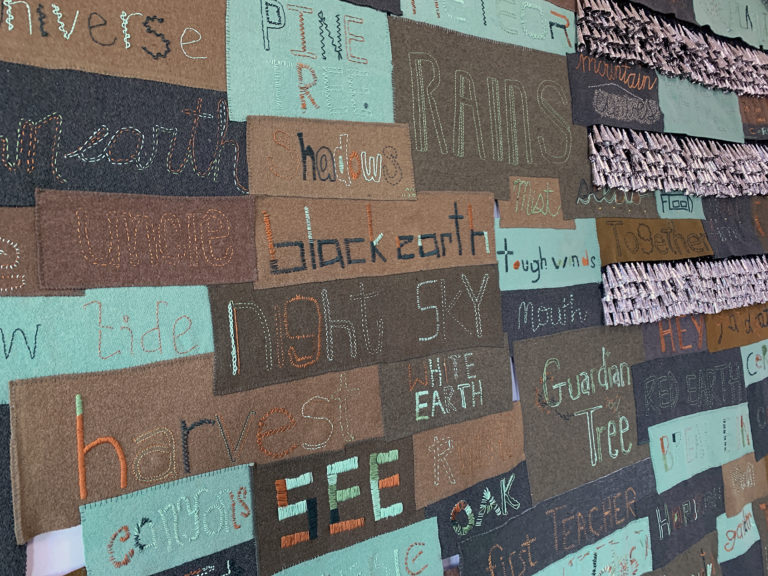

Her most recent show, Turtle Island at Marc Straus Gallery in New York, uses the Iroquois creation myth as its central theme. The two works in the show being added to Tia Collection are Companion Species: Assembly (Auntie and Guardian Tree) which utilizes embroidered words sewn on reclaimed army blankets to evoke family relationships, animals, natural occurrences, and the artist’s memories, while the exact duplicate stacked towers of blankets titled Skywalker/Skyscraper (Twins) tells the story of Kanien’keháka (Mohawk) ironworkers who, since the 1920s, were an integral part of the construction of many of New York City’s tallest buildings and bridges. These skywalkers were known for being fearless and climbed the steel high above the city to erect the infrastructure for one of the most recognized skylines in the world.

Watt holds an MFA in painting and printmaking from Yale University and her acclaims are many. In 2020, she has had works included in a number of exhibitions across the country including the Whitney Museum of American Art in Making Knowing: Craft in Art, 1950–2019; the Yale University Art Gallery in Place, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art; the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum of American Art in Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists and the Heard Museum in Larger Than Memory: Contemporary Art From Indigenous North America. Her work is in the permanent collections of numerous institutions including the National Gallery of Canada, the Portland Art Museum, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian and the Renwick Gallery, the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Seattle Art Museum, US Library of Congress, the Denver Art Museum, and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

In the Seneca and Iroquois creation story, Sky Woman falls from the sky, and as she falls, she is assisted by a motley crew of animals who help her survive on what we now refer to as Turtle Island. In acknowledgment of the way that these animals helped Sky Woman, we consider animals to be our first teachers. I think that when one is raised to think of animals as teachers and also as extensions of us—our relatives or relations—you’re less likely to be able to separate how our actions affect the environment, animals, and the natural world.

-Marie Watt, “In Conversation with Marie Watt: A New Coyote Tale” Art Journal 76, no. 2 (Summer 2017)

Thoughts from the artist

My work draws from storytelling, proto-feminist role models, Indigenous teachings, and biography. I am interested in addressing the enormities of history and memory in one work at a time. Blankets are one of my primary materials. They are objects that we take for granted, but have extraordinary histories of use. Blankets are also personal to me. I am Seneca, and in my tribe and other Indigenous communities, we give blankets away to honor those who witness important life events.

Over the course of scavenging for wool blankets, I have come across twin blanket sets for twin beds. This is an unlikely prompt for “twin” references in our culture, but it is mine. In the Seneca creation story, Skywoman’s daughter dies giving birth to twins, sometimes referred to Right and Left, Sapling and Flint, Daylight and Night Dweller. While these brothers have conflicting natures, they are both considered necessary to keep the world in balance. In a chaotic world, making sense of light and darkness has urgency. I am interested in how “twin” stories—mythical and real—nurture, instruct, disrupt, and affect understandings of the universe, as well as how they suggest connections across time and cultures. These themes materialize into twin columns, titled Skywalker/Skyscraper (Twins). The I-beams reference the Iroquois iron workers (Skywalkers) who helped build Manhattan’s skyscrapers and bridges. At one time, there were so many Iroquois residents in the Boerum Hill neighborhood of Brooklyn, NY, that there was a regular mass held in the Mohawk language.

Marie Watt, Turtle Island

-Marc J. Straus, Gallery Owner and Collector

Marie Watt came to our attention about 7 years ago. We were visiting the Denver Art Museum helping with the plans for Jeffrey Gibson’s first retrospective. My gallery had introduced his work to the market. There was an extraordinary hanging work of Marie’s on display and we had never been to her studio or her galleries in the northwest, but we continued to follow her work.

Then almost 2 years ago we began corresponding and it was an easy decision for me to represent her. The choices made in our gallery correspond to how my wife, Livia, and I function as collectors. We have to love the work, want to own the work and feel it’s fairly priced, and, for the gallery, believe we could contribute to the artist’s career.

Marie Watt is all artist. She has reverence and a keen understanding of her Seneca/ Iroquois culture and translates its beauty and importance into her art that is also beautiful, personal and ultimately universal. Materials are always crucial; which material, and its history. Thus some works include blankets kept by families over generations that are given to her. She often engages groups of women into sewing circles and they bring their own choices of words to the art.

(left) Antipode, Skywalker/Skyscraper (Twins), Companion Species (Is this a pipe?); (right) Companion Species: Assembly (Auntie), Forerunner, Companion Species: Assembly (Guardian Tree)

I opened (my gallery) where I have history, on the Lower Eastside on Grand Street. Across the street on the corner was my dad’s textile store. He was an impoverished immigrant, and I worked there throughout my childhood. I sold plenty of blankets. -Mark Straus

Her use of textiles is a central tenet of her work. Whether a shirt or a blanket, these are items that protect us against cold and external dangers. In Companion Species: Assembly (Auntie and Guardian Tree) she uses reclaimed army blankets, which are used to camouflage and conceal their human counterparts in nature. These earthen green blankets embody landscapes, while holding, protecting, and shielding, and underline the reinforcing link between the object and the narrative.

Reclaimed wool blankets, embroidery floss, thread, cotton twill tape, tin jingles

Thoughts from the artist (continued)

While a part of my process is solitary, another aspect involves collaborating with community. My research and making occurs in both realms. I think of Indigenous community practice as precedent to social practice; it’s a natural extension of my work. My large pieces are often realized in the context of open to the community sewing circles in which participants range from 3 to 93 in age and no sewing experience is required. In exchange for stitches, I give a silkscreen print. It is common for a single piece to have passed through hundreds of hands. Each person’s stitch is like a signature or thumbprint and the intersection of these threads is a metaphor for how we are all connected. There is no obligation to talk while stitching, but stories flow.

Companion Species: Assembly (Auntie and Guardian Tree) were created in sewing circles open to the community that started in October 2019 at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art and Renwick Gallery, and thereafter at the Yale University Art Gallery in conjunction with the exhibition “Place, Nations, Generations, Beings”. At this time, Joy Harjo (Muskogee Creek Nation) had been named the 23rd US Poet Laureate, and the first Native American US Poet Laureate.

Thoughts from the artist (concluded)

The text panels, often embroidered by multiple hands, convey a mash up of what I tenderly refer to as Seneca, Joy Harjo, and Marvin Gaye knowledge about our relatedness, with a focus on words that reveal aspects about human interconnectedness to the environment as witnessed in Harjo’s poems. In the song, What’s Going On, Marvin Gaye calls out, “Mother, mother, Brother, brother, Father, father, Sister, sister.” In my mind, this is not merely familial, it is a call to humans, animals, and the environment.

When the pandemic hit, I chose to re-envision what sewing circles might look like in distancing pods. I reached out to past sewing circle participants and my word of mouth networks to gauge interest. Forty sewing circle packets were sent out and 100 participants stitched 80+ panels. Panels were further completed in my studio and composed into this work, twin-like, as they are from the same cloth and in proximity want to talk together, but also stand alone as individual companions do. Because army blankets are used to camouflage and conceal their human counterparts in nature, I see these blankets as embodying landscapes while holding, protecting, shielding bodies often in the land. For me, these greens are earthen. The jingles, bell-like tins, make music when danced in pow wows, but are also a reminder of the life of these objects and words. The three bands also recall the points or fingers that imply the value of early trade blankets, ledgers as information portals, and stripes that have a deep history in painting and nature.

In my work, I seek to break down boundaries and obstacles between center and periphery. My work actively disrupts the way the art world expects people to work in contemporary art, in part by making the process participatory, accessible, and open.