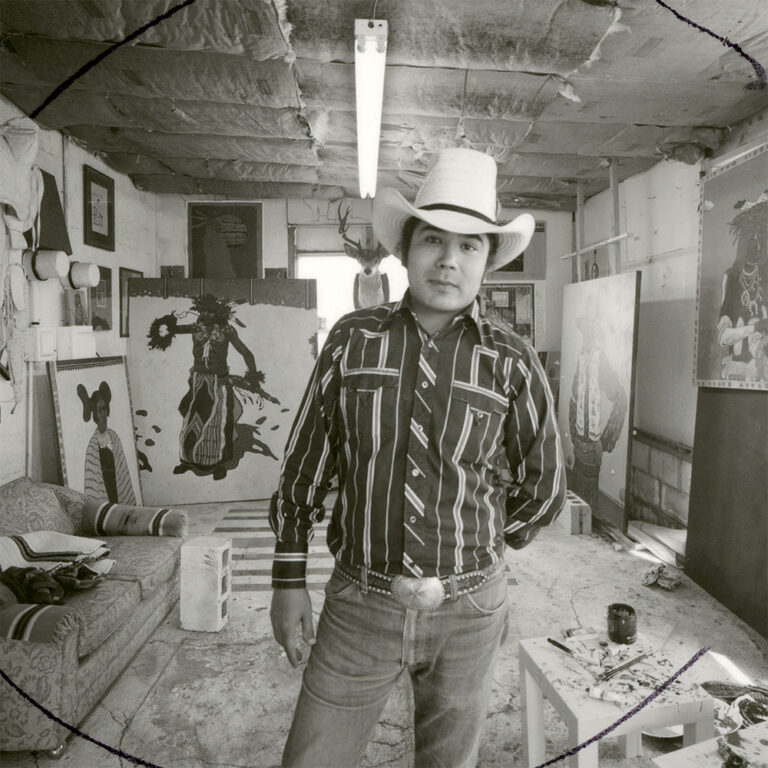

American artist, poet and musician T.C. Cannon, who was known for his boldly contemporary depictions of Native American subjects, continues to influence and shape Indigenous arts since he arrived on the scene as a teenager in the 1960s. Born Tommy Wayne Cannon, the Gáuigú (Kiowa)/Kadawdáachuh (Caddo Nation) painter was born in Lawton, Oklahoma to Indigenous farmers. Given the Kiowa name Pai-doung-a-day, meaning “One Who Stands in the Sun,” Cannon expressed an interest in art at a young age and began his formal art education at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico. There, he studied under Payómkawichum (Luiseño) artist Fritz Scholder, laying the groundwork that eventually led to their landmark 1972 show, Two American Painters: Fritz Scholder and T.C. Cannon, held at the now Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. Attending IAIA also exposed Cannon to a broader spectrum of artistic styles and philosophies outside of the scope of his Native Oklahoman circle, fueling his desire to push the boundaries of what was considered “Indigenous” art at the time. Today, we recognize his work by his unmistakable use of bold color, dynamic composition and insightful, often electric cultural commentary on Native identity in the modern world.

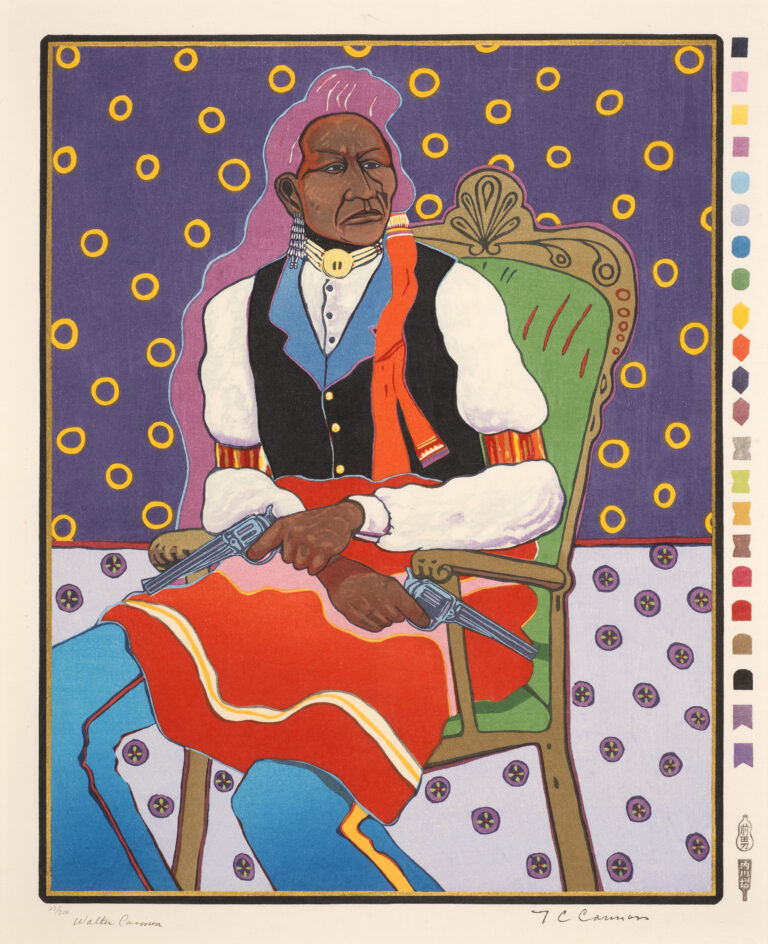

His striking paintings and prints often feature Native figures in modern, western attire, coupled with traditional Indigenous symbols and imagery. This marriage of the traditional and contemporary, a distinctly rebellious and, at the time, startling blend of motifs, challenged viewers to question Native stereotypes and to consider the dynamic nature of cultural identity. Cannon’s print, Memorial Woodcut Portfolio – Two Guns Arikira (1976), exemplifies this unique style. Cannon depicts an Indigenous man seated on a Victorian drawing room chair, set against a vibrantly colored and patterned background. The figure’s flowing pinkish purple hair is coupled with a stern countenance, beaded jewelry, a western vest and collared shirt, and two long-barreled revolvers. This fusion of elements reflects Cannon’s view of Indigenous people as fluid and evolving, rather than static or confined to the past. The painting of this same subject matter is now in the collection of Museum of Modern Art, New York.

An Indian painting is any painting that’s done by an Indian. … [but] it seems beside the point to call a painting Indian just because the artist is an Indian. … People don’t call a painting by Picasso a Spanish painting…

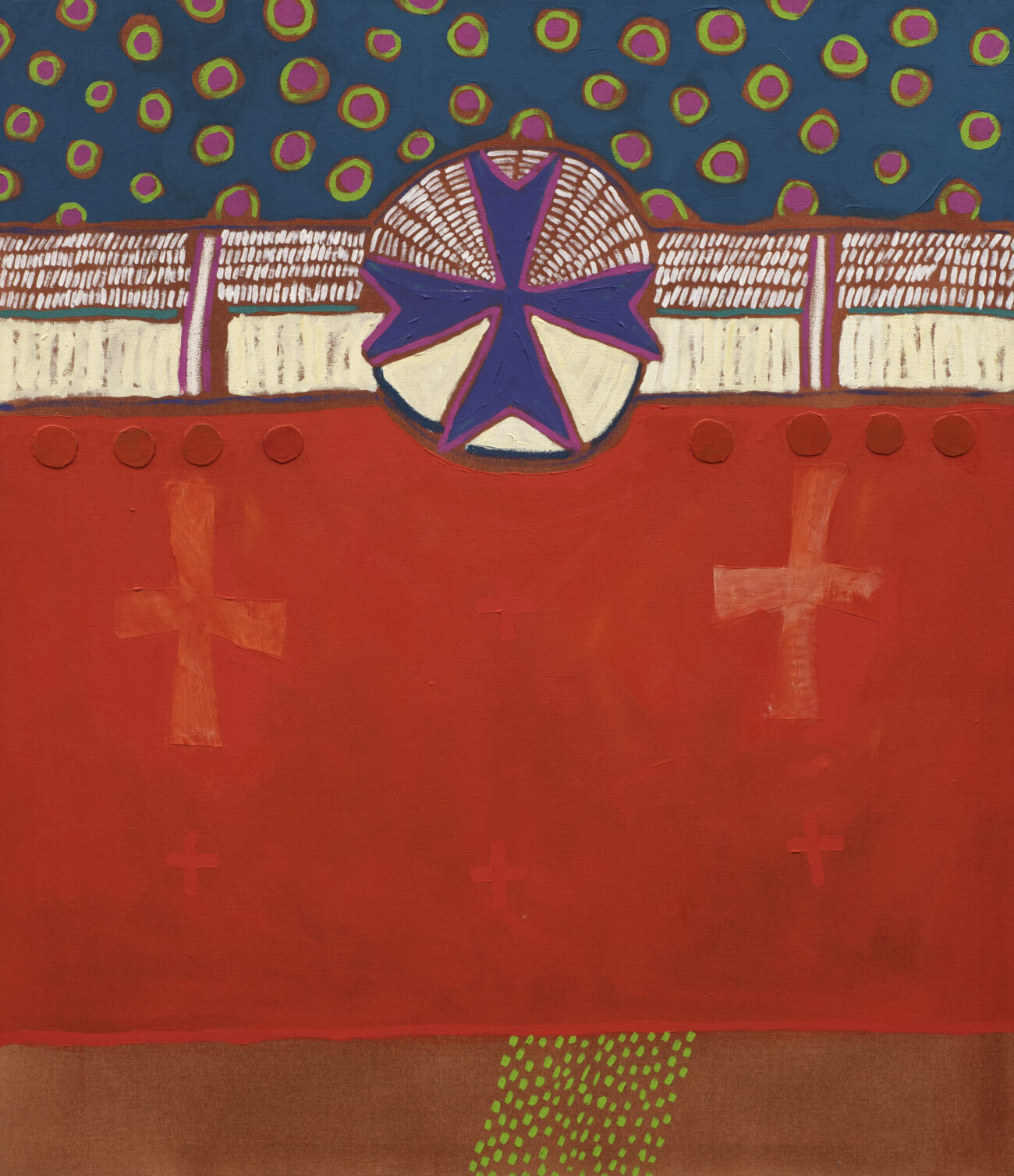

While Cannon’s work as a whole examines the romanticized portrayal of Native Americans in mainstream media, and offers a nuanced and authentic representation of Indigenous life, he also challenged his own style throughout his career. Known for his deep hues of red, yellow and blue, Cannon opted for a starkly white background in Pueblo Woman Dancer, made between 1972 and 1978. However, his implementation of scrambling—a painting technique in which an opaque layer of paint is dry-brushed over a darker background—resulted in a rich and textured effect. He also portrayed the subject’s face obscured, and in shadow, as if to offer her privacy from the eyes of the viewer. The ridged frame additionally acts as a protective border, emphasizing the woman’s autonomy. With one hand on her hip, she seems to warn against the commodification of her person, or the type of gawking “white” gaze that Cannon critiqued throughout his life and work.

In William Wallo and John Pickard’s book T.C. Cannon, Native American: A New View of the West, the authors describe another work that addresses the romanticization of Indigenous people: “Another comment on the war of the sexes is found in the vibrant and sardonic comedy “Red Tipi Warrior (1973)”, a look at the fierce Plains tribesman in repose. All the romantic emblems of the rampant noble savage are present—the horned headdress, the painted face and body, the pistol, the soft hide to recline on. But they are all slightly askew. The horns are cock-eyed, the body pot bellied, the warrior less than menacing. Even the eccentric little dog coming around the absurdly red tipi seems to have nothing to fear. The lush carpet of grass suggests an invitation to a nice long nap in the near-parody of a ‘man’s world’ in the old days. If this is another Cannon disguise he can hardly keep a straight face. ‘Dream On,’ the artist seems to say.”

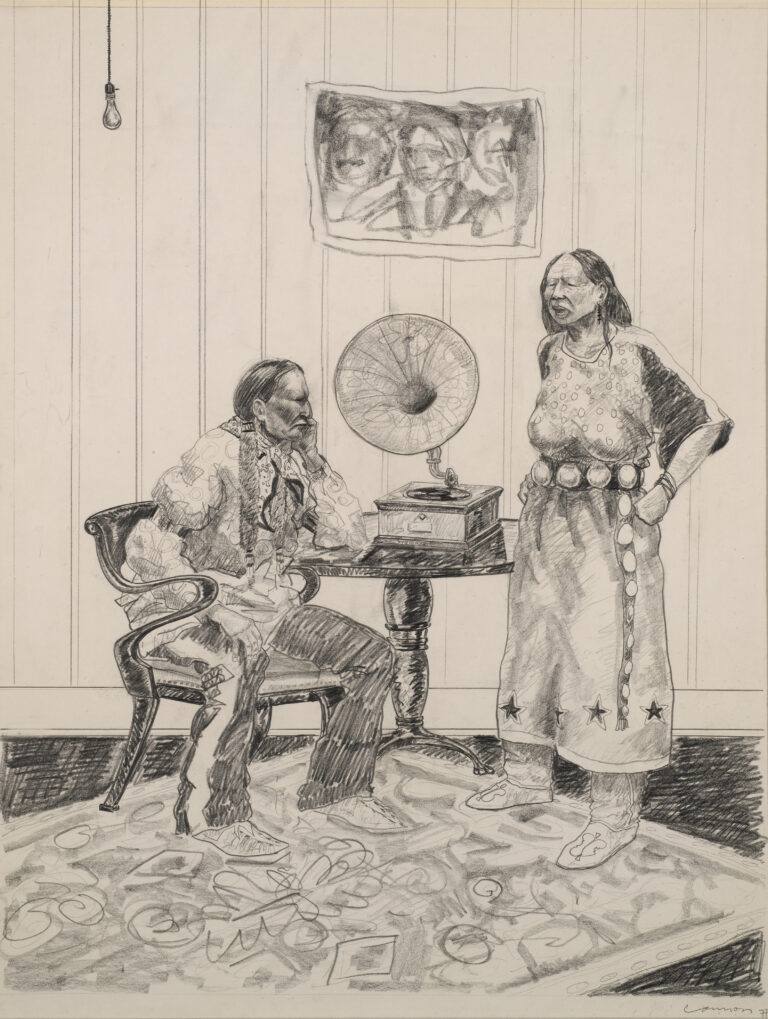

Cannon was also known for his love of music—the artist played guitar, wrote songs and sang, and was known to blast Bob Dylan while working in the studio. In 1978, The Santa Fe Opera Guild commissioned his painting A Remembered Muse (Tosca) for the cover of the Santa Fe Opera’s 22nd season. The painting and drawing title come from Giacomo Puccini’s opera, Tosca. Shoshana Resnikoff writes in TC Cannon: At the Edge of America – “A Remembered Muse (Tosca) maintains a balance between the poles of easy affliction and urgency. The couple has everyday intimacy, relaxed and comfortable in the interior confines of their home, while the abrupt inclusion of the political poster exerts pressure on the scene. The work is also subtly personal: Cannon’s passion for music extended beyond the Santa Fe Opera Guild and his poem “In the Wonderful World of Opera” attest. Historic and contemporary, welcoming and confrontational, A Remembered Muse (Tosca) captures the full range of Cannon’s work in a single image.”

Later in 1978, Cannon’s life and career was tragically cut short when his car drove off a road outside of Santa Fe. His impact and many contributions to the world of art endures. Cannon’s work continues to inspire contemporary Indigenous artists in profound and impactful ways. Artists such as Wendy Red Star, Jeffrey Gibson and many others are inspired by his legacy, also using their work to challenge stereotypes and redefine what it means to be Indigenous today, and ensuring that their voices are sung alongside Cannon’s.

Written and designed by Sarah Greenwood.