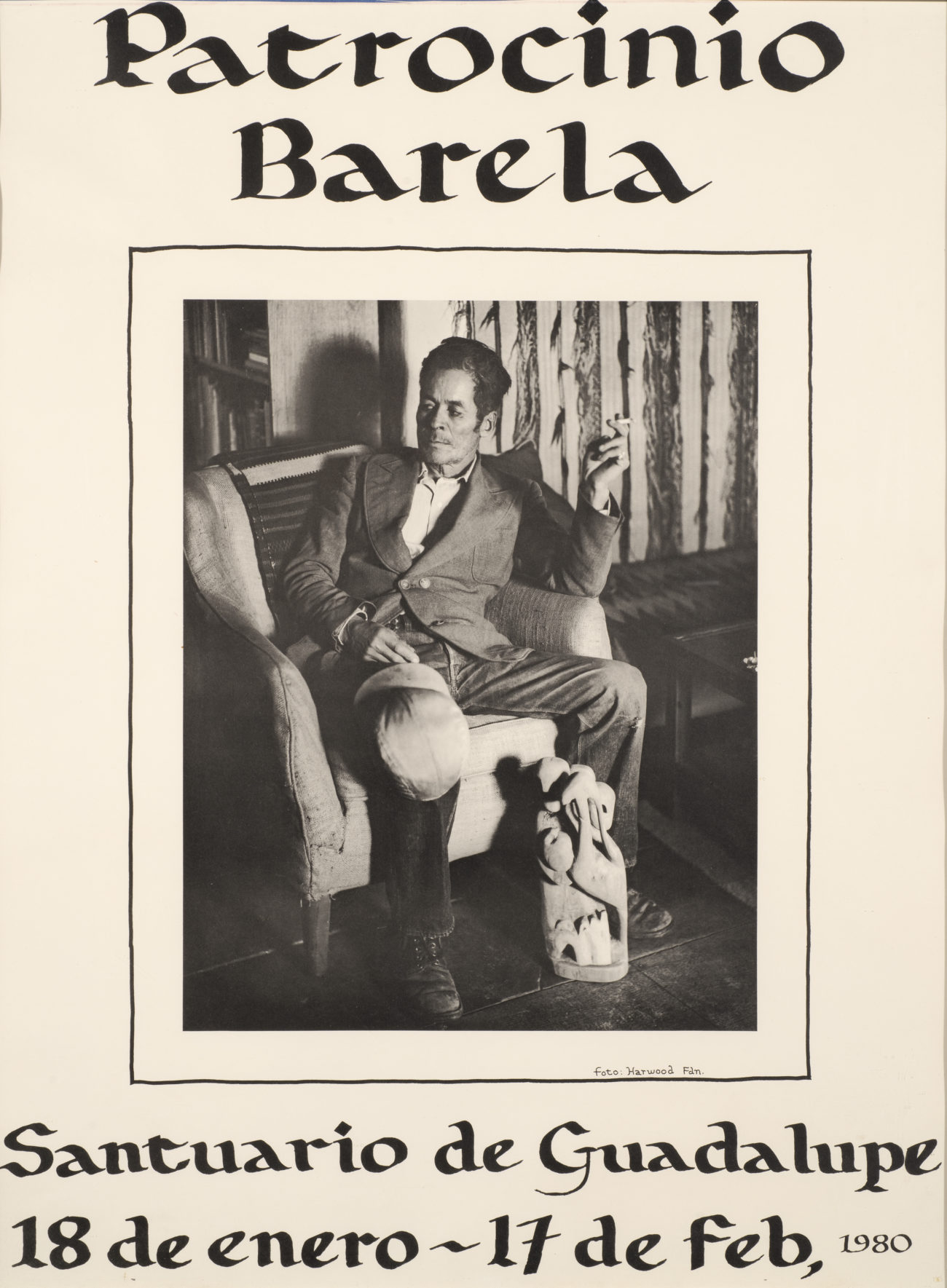

“Discovery of the year.”

James Hart Photography

Born in Bizbee, Arizona, Patrociño Barela moved to Taos, New Mexico with his family at the age of 8 years old. His father worked at lumber yards and sheep farms as a laborer and, once old enough, Barela began working with him. Barela only attended a few weeks of school and, as a result, never learned to read or write. He would later be known as the artist that Time Magazine called the “discovery of the year.” At the age of 11 years old, Barela moved to Denver on his own to find more work as an itinerant laborer and then later working across the southwest.

Eventually, he did return to Taos in 1930 and married Remedios Josefa Trujillo y Vigil shortly after. Remedios was a widow with 4 children from a previous marriage. As the country sank further into the great depression, Barela found that he needed to find ways to make more income. Since he had been carving wood all his life, it was a natural to fall back on his skills to create sculptures.It was not until he began working for the WPA as a laborer that he was discovered by Russell Vernon Hunter, a fellow artist and state director of the WPA in New Mexico, that his career as an artist took off. Russell submitted Pat’s work for the Federal Art Project and, in 1936, he was featured in an exhibition at Museum of Modern Art in New York called New Horizons American Art.

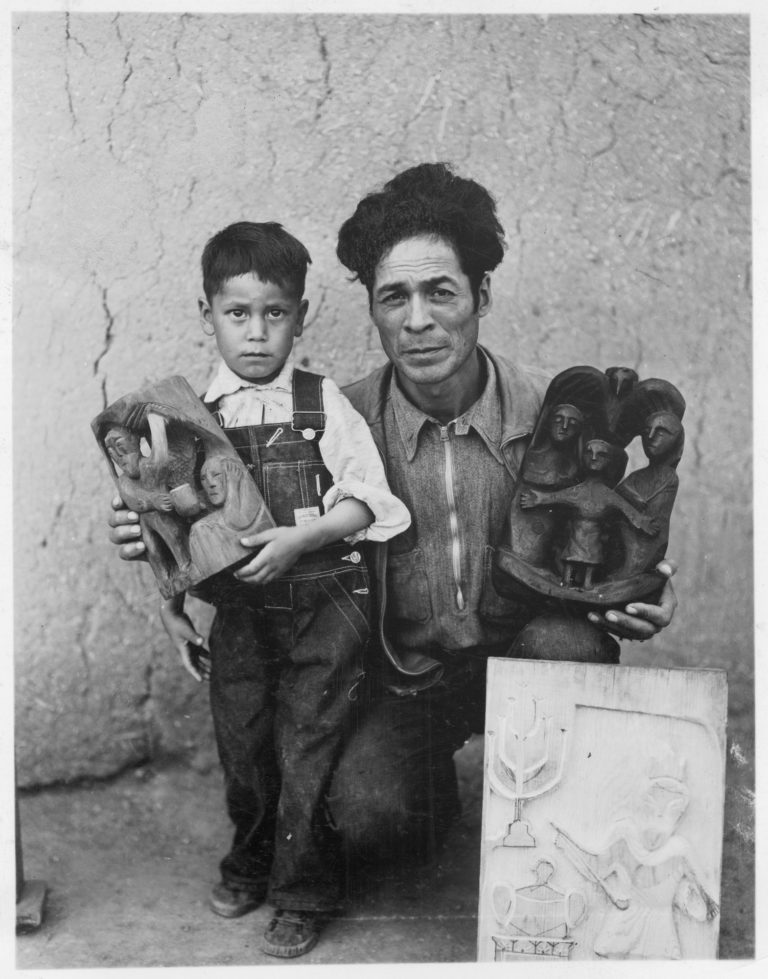

“Patrociño Barela, with three of his wood carvings and his little son. This humble day laborer of New Mexico is the most dramatic discovery made in American art for the past several years. Seven of his remarkable wood carvings are included in New Horizons in American Art, an exhibition of outstanding work done under the Federal Art Porject which will be on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, until October 12.NEW HORIZONS IN AMERICAN ART, Federal Art Project Exhibition, Works Progress Administration, Sept. 16, 1936 to Oct. 12, 1936, The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York.”

Research photograph associated with the exhibition, “New Horizons in American Art.”

James Hart Photography

Barela’s work was often described as “true primitive” or “naïve genius.” He was creating modernist work without realizing there was a modernist movement happening elsewhere in the world. In his reality, it was his style which brought light and change to a long standing New Mexican art form. His bultos were unlike others in many ways. They were often carved from one piece of wood, didn’t feature paint and were much more abstract. Traditionally, bultos are carved from multiple pieces of wood, covered in gesso and paint, and made by Santeros or Saint Makers (members or caretakers of the church). For hundreds of years only men could make bultos, but now women, including Barela’s granddaughter, Patricia Barela Rael, carve bultos.

Barela was known for following the grain of the wood, incorporating knots from the local New Mexican wood into his pieces. Certain shapes and themes called to him and he was known for depicting families, especially the Holy Family. He began to step away from only creating religious pieces to those about the process of human life. Speaking to Time Magazine, he described the four stages of man starting as a boy filled with hope and dreams; followed by a young man with the hopes of opportunities ahead of him; then a middle-aged man hoping to set a good example for his son and, lastly, an old man hoping he has left a strong legacy behind him. Barela was now carving works sentimental to him.

James Hart Photography

After the WPA ended, Barela went back to labor jobs and sheep herding. It was not until the 1950s that he began to seriously carve again. He went on to be represented by several galleries in Taos and interacted with other Taos Modernists on occasion. In October 1964, Barela died in an early morning fire in his shop, where he had fallen asleep while carving. He created over 1,400 works during his career and his artistic legacy has inspired generations of New Mexican Santeros. His granddaughter spoke with The Santa Fe New Mexican in 2014 about beginning to carve, ““it felt really good. I felt my grandfather close to me. I felt like he was there inspiring me and nudging me along to finish what I had started.”

Written and designed by Sarah Greenwood.