In the work of Nicholas Galanin, sharpness is both metaphor and method. Born in Sitka, Alaska, and of Tlingit and Unangax̂ descent, Galanin is one of the most searing voices in contemporary Indigenous art. His practice, which cuts across sculpture, installation, performance, and sound, carves space for Indigenous agency within the dominant narratives of American art and history. With a visual language that oscillates between the poetic and the political, Galanin confronts cultural appropriation, colonial violence, and the uneasy entanglements of identity and image.

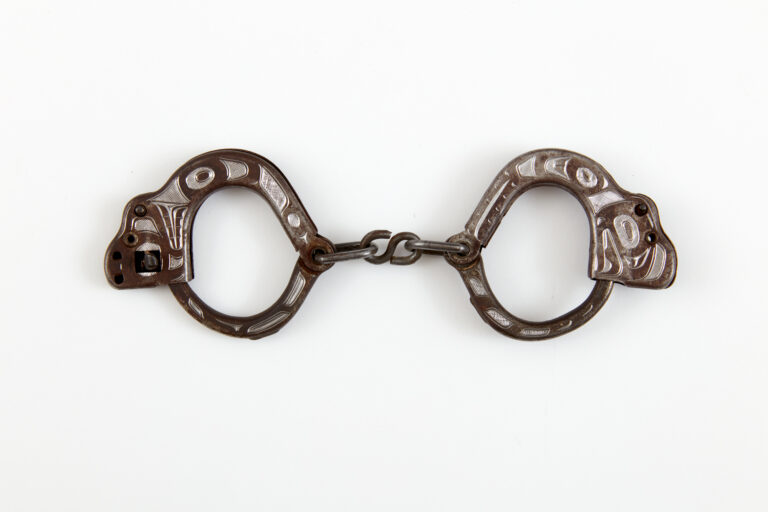

In Language removal tools for Indian Children, Sheldon Jackson (2023), Galanin presents a pair of child-sized iron handcuffs engraved with traditional Tlingit formline designs. The work’s title, deceptively benign, forces a collision between the aesthetically beautiful and institutional brutality. The bracelets are a reminder of both the commodification of Indigenous adornment and the grim legacy of residential schools, where Indigenous children were severed from their languages, families, and cultures. As with much of Galanin’s work, the object is deceptively elegant, but carries a violence that is systemic, historical, and ongoing.

This dynamic of duality–tradition versus tourist fantasy, authenticity versus replication–echoes through The Imaginary Indian series. In The Imaginary Indian (Arts and Crafts), a towering carved totem pole is clad in colonial-inspired wallpaper, its surfaces wrapped in delicate Victorian florals. Later versions, such as The Imaginary Indian (Garden), feature imported, non-Native totems manufactured in Indonesia. The result is a critique of the global market’s appetite for flattened, consumable ideas of Indigeneity, where sacred objects become decorative kitsch for lobbies and gift shops.

That tension–between violence and veneer–reaches a point in Exist in the Width of a Knife’s Edge (2023), a work included in the artist’s recent solo exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Sixty porcelain daggers hang in mid-air, each one adorned with Russian-inspired blue-and-white floral motifs. Suspended in a ghostly, almost sacred arrangement, the daggers evoke both weaponry and ceremony. They reference the imperial histories that divided the Aleutian Islands between Russia and the United States, while the porcelain–so fragile, so collectible–speaks to the precarity of Indigenous land, life, and memory under the weight of settler empires.

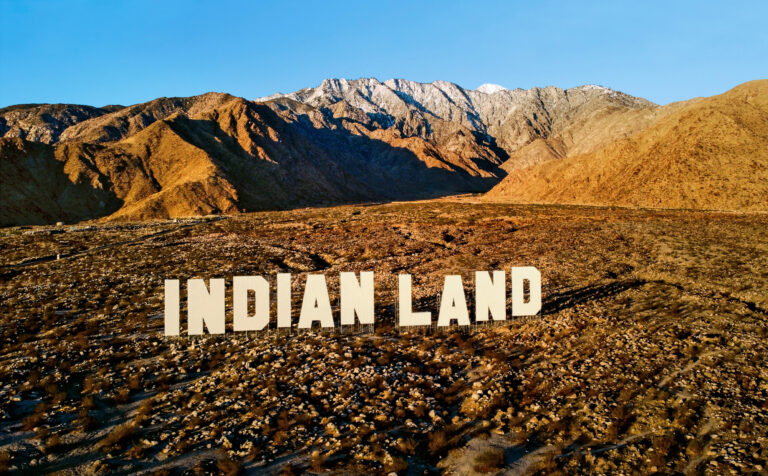

Galanin’s Never Forget (2021), installed near Palm Springs, is at once a billboard and a battleground. The piece boldly restages the Hollywood sign as “INDIAN LAND,” towering over a desert landscape shaped by real estate speculation and colonial development. The gesture is clear: this isn’t a passive land acknowledgment, but a call for land back. Monumental and unflinching, Never Forget strips the polish from pop culture’s mythologies and returns the land to its unceded truth.

Ancestral Map of Return is the first in a new series of hide paintings that extends the ongoing Architecture of Return project–an evolving body of work that imagines and charts the escape routes for Indigenous ancestors and cultural belongings held in non-Indigenous institutions. This work takes the form of a star map, invoking Indigenous celestial knowledge and its expansive understanding of the night sky–not as metaphor, but as methodology. Each point of light on the hide marks the presence of an Indigenous person whose remains are held in museums, universities, and other colonial collections around the world. It is a map, but also a memorial and a call: for every speck of light, there is a lineage, a homeland, a community awaiting their return. This work functions as a plan for wayfinding, a cartography of homecoming, and a statement of belief–that return is not symbolic, but necessary for collective liberation.

The burden of cultural distortion is made literal in Artist carrying the weight of imitation (after Christ carrying the cross). In this performance, Galanin hauls a replica totem pole–a mass-market caricature of Indigenous iconography–through public space. The visual echo of Christ’s crucifixion isn’t merely symbolic. It positions the Native artist as martyr, forced to shoulder the weight of settler misrepresentation. Here, Galanin plays both actor and activist, exposing how Indigenous identity is too often rendered through the lens of colonial fantasy.

Taken together, Galanin’s work forms a constellation of interventions–material, conceptual, and fiercely personal. His art does not ask to be understood within the framework of Western aesthetics; it demands a reorientation of that framework itself. Whether casting daggers in porcelain, engraving trauma into iron, or staging reclamation in the scale of monument, Galanin operates in the tension between what is seen and what is silenced. And it is in that width the knife’s edge–that his art insists on Indigenous presence, persistence, and power.

Written and designed by Sarah Greenwood.