Since its inception, Tia Collection’s mission has included pointed efforts to capture and record the stories and intentions of artists represented in the collection, including their oral and written histories. Most recently, Tia sat down with internationally recognized conceptual and textile artist Karen Hampton, who often refers to herself as a griot (storyteller) and engages with race and kinship within the African American diaspora. Read more below for the stories behind the artist’s work in the collection, and how Hampton’s family tree, interests and research continues to shape her practice today.

Want to hear the artist’s story in her own words? Listen to the full transcript here.

Invisible Child was created in 1996. At that point in my life, I still was very much in the middle of raising kids. I had a seven year old and a 15 year old, so, lots of kid’s stuff. As a result, my work had changed dramatically. 1991 was when my work really, really changed because I was doing deep sea diving into myself, trying to understand the textile world and why I didn’t quite fit in. The work I was doing was very much the kind of work that was within the field; but in the 1980s, I was told three times that someone thought I hadn’t done the artwork, and that I must be fronting for someone else. That was because people had never seen anyone who looked like me doing textile work….I was also aware of the fact that throughout most of the world, people of color have been making, as far as I’m concerned, the most beautiful textiles.

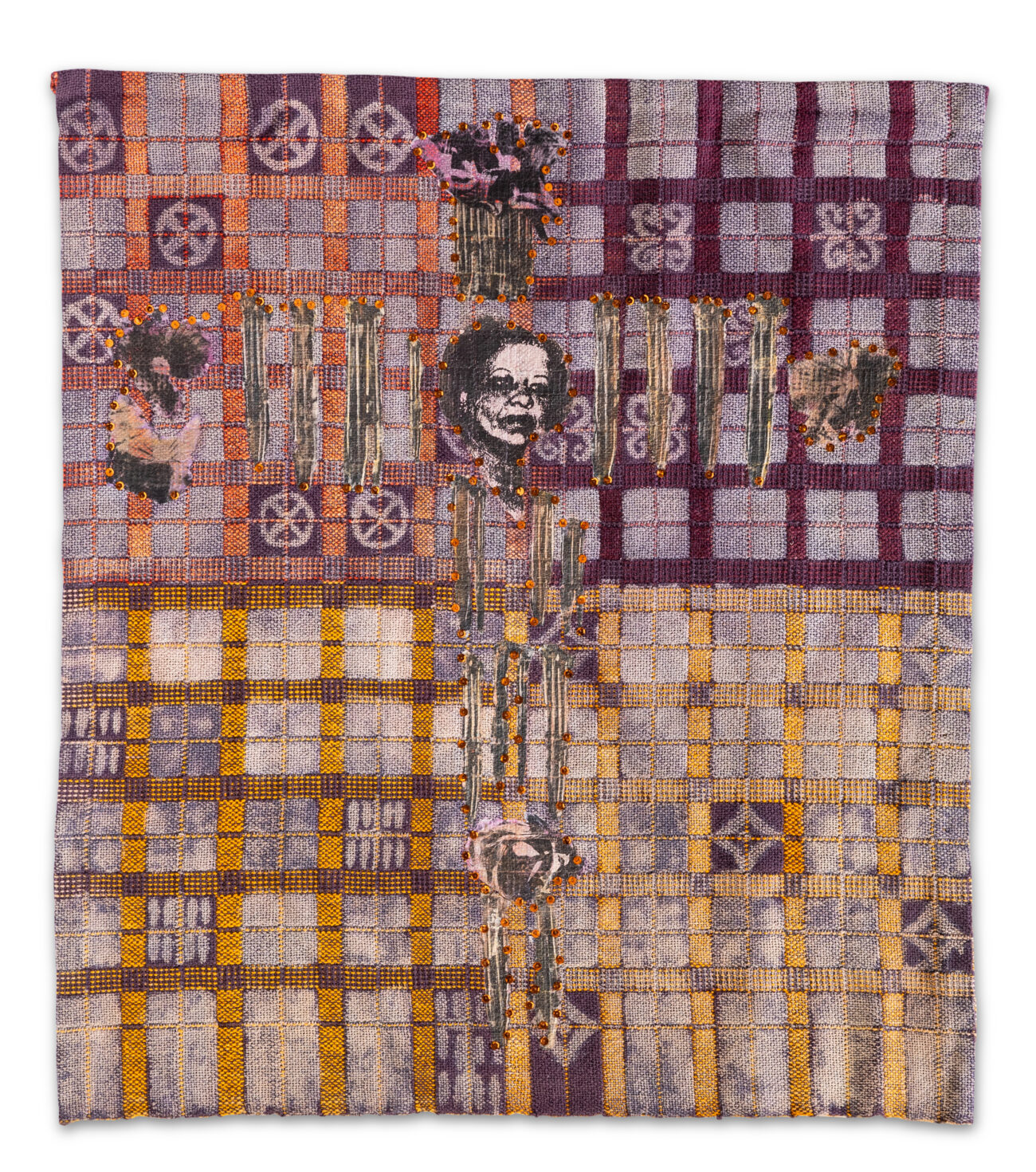

It was coming down to something that I knew in many other contexts. I understood racism really well, but I didn’t understand how it was affecting my world because art was a savior for me. By the time 1996 came along, I had gone through a phase of making work that was inspired by kente cloth [Ghanaian textile made of hand-woven strips of silk and cotton, originally reserved for royalty], in that the only rule that I used was the width of my strips. Kente cloth is between one and a half and seven inches wide for each strip. That was the only guide that I was using. I first started doing them in strips, and then I started playing with the strips more and working, as you can see, in quadrants. Then, I was using my textile techniques, which you see in Invisible Child, 1996, and Devotion, 2002, by doing a painted warp or two painted warps…that’s called double weave.

Invisible Child is the second piece that I made using image transfers. This was something that I had been struggling with because I really felt that I needed, as an artist, to be able to use portraits and the human figure….It took me a long time to be brave enough to put images on a hand-woven work because where I was trained, it is blasphemy to do something like that. It took a lot, but I came up with a technique for it. Part of using the figure was to be able to have complex subjects.

Invisible Child is about when you’re Brown, whether you’re light skin or you’re dark skin, you’re still invisible. I used an image of myself as a baby and worked with it. It was before the days of Photoshop, so I was making trips to Kinko’s in the middle of the night to do all of my enlarging. The whole thing about permission and rights to use images—I cut out the headache and just worked with family photos. I also had enough stories to tell from my family.

In Devotion, 2002….I think it’s mystical to most people if they don’t quite know what it is about. It was a remembrance piece for my grandaunt, who had been my primary caregiver as a child. I believe I’ve done three pieces that have been in remembrance of her. She was an incredible, spiritual person that was disabled and was the most able-bodied person around. She died when I was 17.

Devotion has ties to New Mexico. I didn’t have any thoughts of ever doing a piece for my grandaunt at the time, but during my first trip to New Mexico, I visited Chimayo. I went into the room with the altar of crutches and that was what really inspired what I wanted to do for her. In Devotion, you see the crutches laid out. She loved flowers….In the early 1990s, I started giving myself exercises to figure out what my symbols were. These [crutches and flowers] were just some of what was starting to show up.

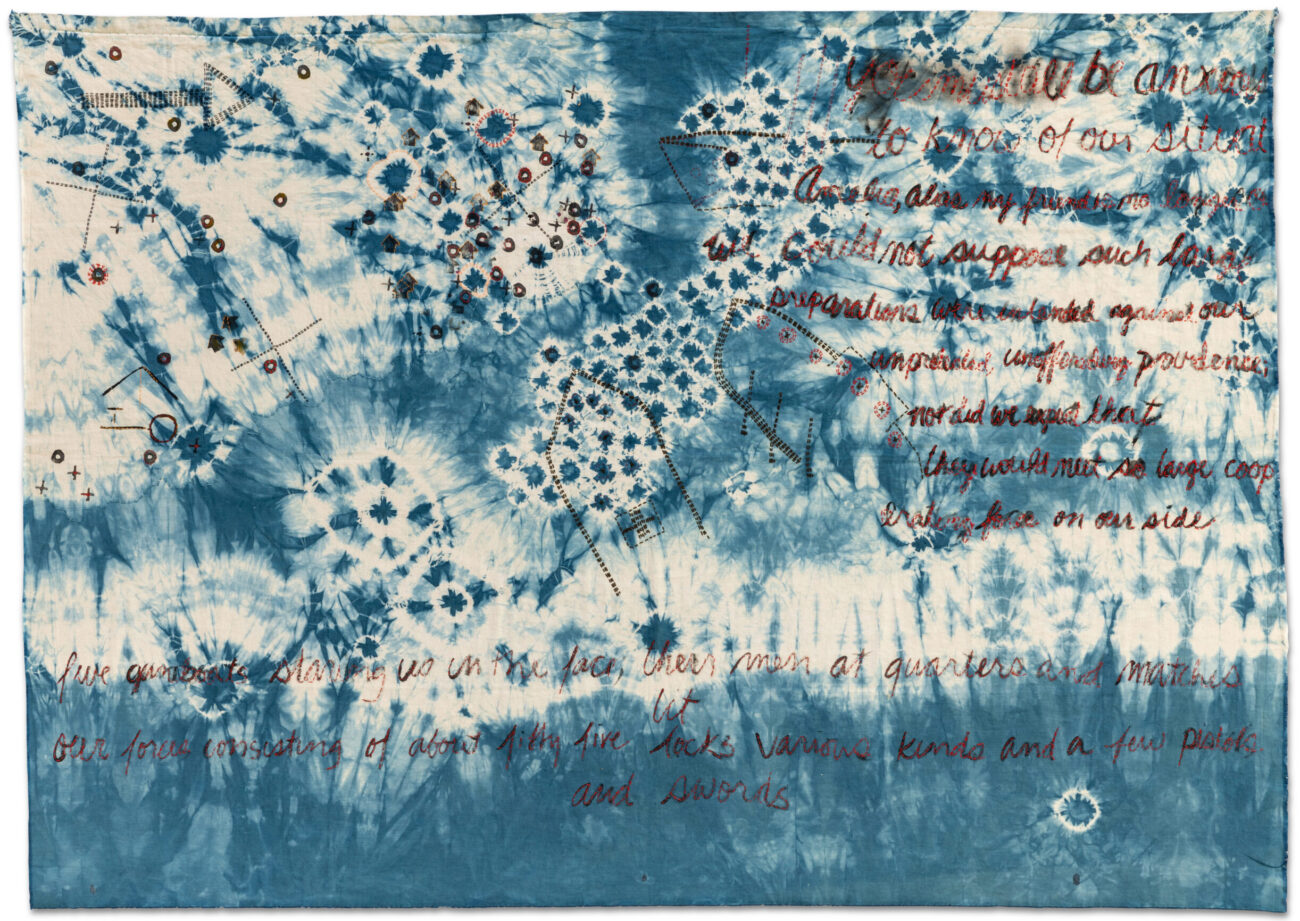

I’m going give you a little background about Patriots War, 2008. I went to graduate school between 1998 and 2000, and I was still on this quest trying to understand where I fit into this movie of life. In graduate school, I needed to know a history, I needed to know—how did I end up at this point in history, being a weaver in a world where there are almost zilch African American weavers? And so my research in graduate school was on African American women in textile production from 1750 to 1830. I did field work; I visited 11 plantations and other historical sites at a time when Black people did not go to plantations. I found that the land was speaking to me and there were stories within the landscape. My research was in North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia in the low country. So, that was wonderful. I was really happy in my artwork, and I loved what I came up with.

About six months later, my father called and he told me that a cousin he hadn’t spoken to in 40 years had called him. This cousin only lived 40 miles away….In his retirement, this cousin became the president of the Genealogical Society of Riverside County in California. My father went to brunch at his house and he pulled out manumission papers—he pulled out all of these things that dated the family. Number one, I had no idea that my grandfather was born in Florida. I knew nothing about Florida. My father told me this and so I asked for the dates, and it was the exact same period that I had done my research on in graduate school….

I found out that I had this wealth of history in my own family that was so different than any story that had ever been explored, or that was ever seen for the African American experience. It’s been about 22 years since I’ve been working on compiling the history, and I go back to it periodically.

[I discovered] my ancestor eight generations before me was British. His name was George John Frederick Clarke, and his history was under Spanish Florida….George had been enlisted by the governor of Florida to plot out the town of Fernandina, Florida, which sits right along the Saint Mary’s River at the very, very top of Florida. It’s on Amelia Island. The Saint Mary’s River was a very important trafficking road. After years of doing this research, it finally hit me. When it became illegal to bring enslaved people into the U.S., they were still bringing them in and they were bringing them through the Saint Mary’s River.

George was sent there to go and create order. And so he created all of the streets and he also created the specs for the sizes of the houses everyone would have. There are maps today where you can see everyone’s house. The most important part, when he was on the shore, is the fact that everyone was prospering with his order. It was a place where there were free Black and white and Hispanic people all inter-living and marrying.

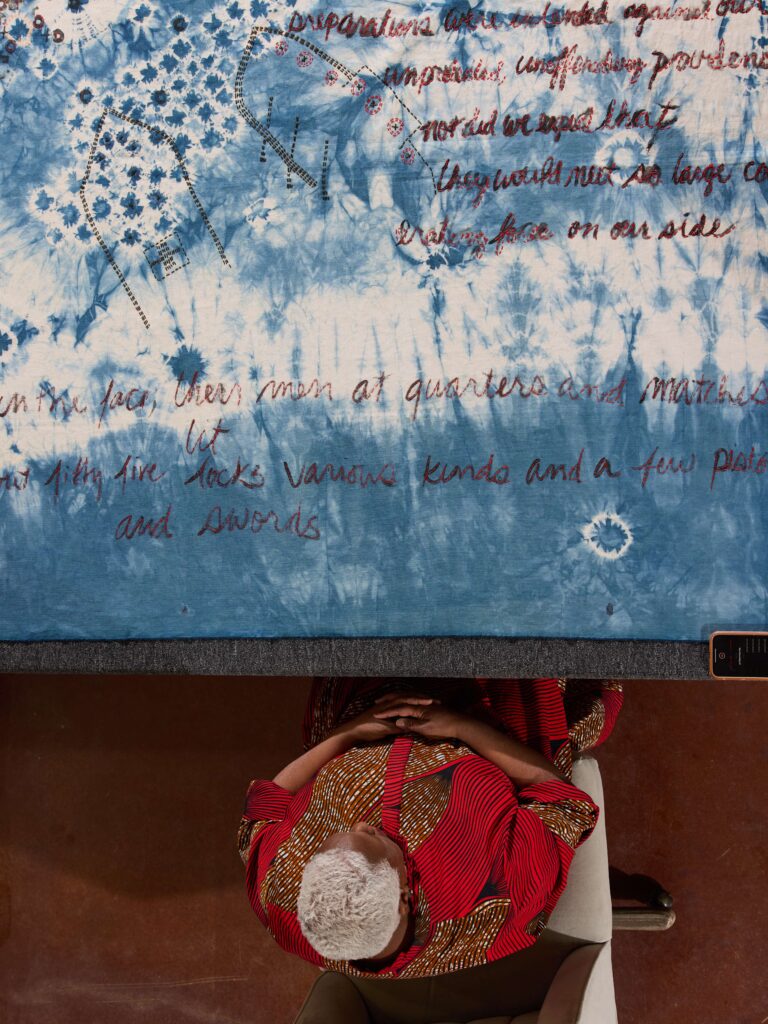

In 1813, the gunboats are coming in from South Carolina. And so, written on Patriots War, in thread, is the letter that George sent to the governor because he realized that this was a very sad moment. He begins, ‘I’ll be anxious to know of our situation. Amelia, alas my friends, is no longer. We could not suppose such large preparations were intended against our unprepared and unoffending province; nor did we expect that they would meet such large cooperating forces on our side.’

This is sadness. George had been trying to create a world where people fit together, and this is the sad moment of realization. And so, no guns were fired….My family was taken to live on a reservation on another island. They destroyed everything that was there in Fernandina.

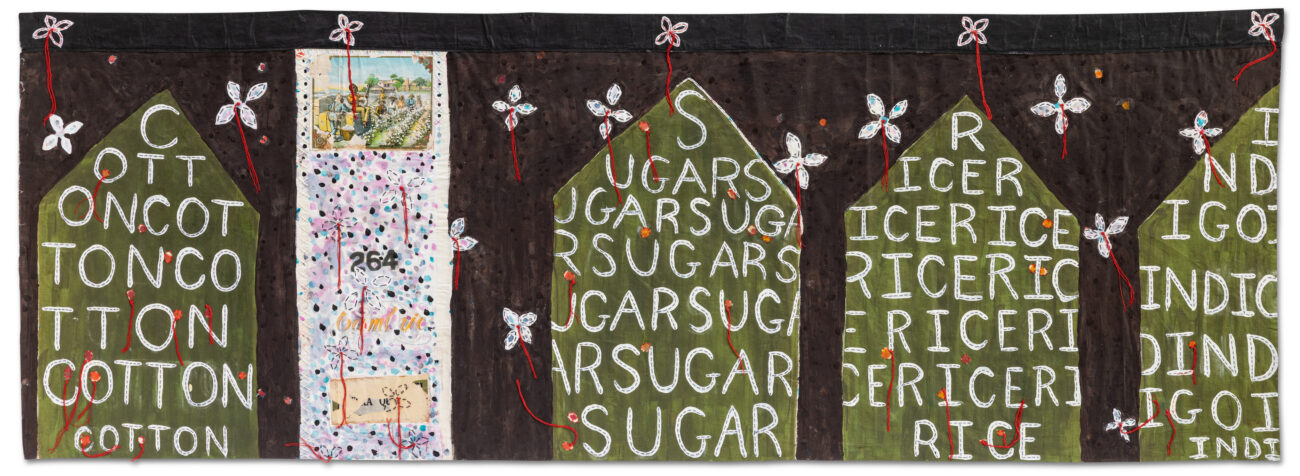

You have to understand that people, for whatever reason, give me all sorts of weird things. I don’t think I ever met the person who sent me this piece of fabric used in Four Pillars of Slavery, 2022. This piece of fabric, when I got it, was kind of an ecru color. It had this label on it and I just did not know what on earth this thing was….So I sat with it for a long time. There’s something about that label. The label is telling me something. It made me think of the big house, and using houses is kind of a thing for me. It’s been something I have been obsessed with since I was a little girl. I had a playhouse as a little girl, and that playhouse could become all sorts of things.

I was thinking about the history of slavery and the history of these crafts, because all of the studying and everything I’ve done has really been the lesson of economics. Everything else is just the byproduct. But it comes down to the economics of how and why slavery worked. I really thought about these different houses. Indigo was the second largest field crop in the U.S.; cotton came after indigo; rice was the largest; sugar was the largest in the world, and then cotton later. In Four Pillars of Slavery, these red flowers coming down are a kind of neutralization. I do that in a lot of work: neutralize the evil. That’s what I was doing with these symbolic flowers coming down. Planting seeds of a different sort.

(This) all goes back to my grandaunt. She was a storyteller and I was her confident. She told me stories about Jamaica all the time and so I learned to visualize stories. That gave me the impetus to start really digging into stories. I didn’t know anyone at the time that used stories. I literally said to myself, if Picasso could have beautiful women as his muse, then I could have history as mine. My whole life is kind of this quest to understand us living on this earth. As far as I’m concerned, no one has any more a right than anyone else.

This interview transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Hampton’s artwork is held in the collections of the Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art, Hamilton College, Clinton, New York, and the Honolulu Museum of Art, Honolulu, Hawaii. In 2008, Hampton received the coveted Eureka Prize from the Fleishhacker Foundation and was named the 2022 fellow by the American Craft Council.

A special thank you to Karen Hampton and KOURI + CORRAO gallery.

Written and designed by Sarah Greenwood.