Jagdish Swaminathan (1928–1994) occupies a pivotal role in the narrative of Indian modernism, a figure whose work pushed the boundaries between tradition and modernity in postcolonial India. His significance lies in the way he rejected conventional artistic hierarchies, merging indigenous tribal motifs with the formal language of modernist abstraction. Swaminathan’s practice wasn’t just about aesthetics—it was a political and philosophical inquiry into what it meant to create art in a newly independent nation, conscious of its cultural heritage but also navigating global currents.

Born in 1928 in Shimla, the capital of the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh located in the Himalayan foothills, Swaminathan’s path to art was shaped by his political activism. An early association with the Communist Party of India influenced his belief that art could be a form of resistance. Though he initially studied as a journalist, Swaminathan turned to painting, attending Delhi Polytechnic and later the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, Poland. His exposure to both Indian and European art forged a vision that sought to reconcile these two seemingly disparate worlds. In 1963, Swaminathan is best known for founding Group 1890, an avant-garde collective that sought to move beyond the two dominant streams of Indian art at the time: the romanticized nationalism of the Bengal School and the Western-oriented approaches of the Progressive Artists’ Group. In the manifesto he wrote for the group, Swaminathan articulated a need for art that was uniquely Indian without succumbing to nostalgia or Western mimicry. Group 1890 rejected the idea that Indian art had to define itself through external paradigms, advocating instead for a modernism rooted in Indian realities.

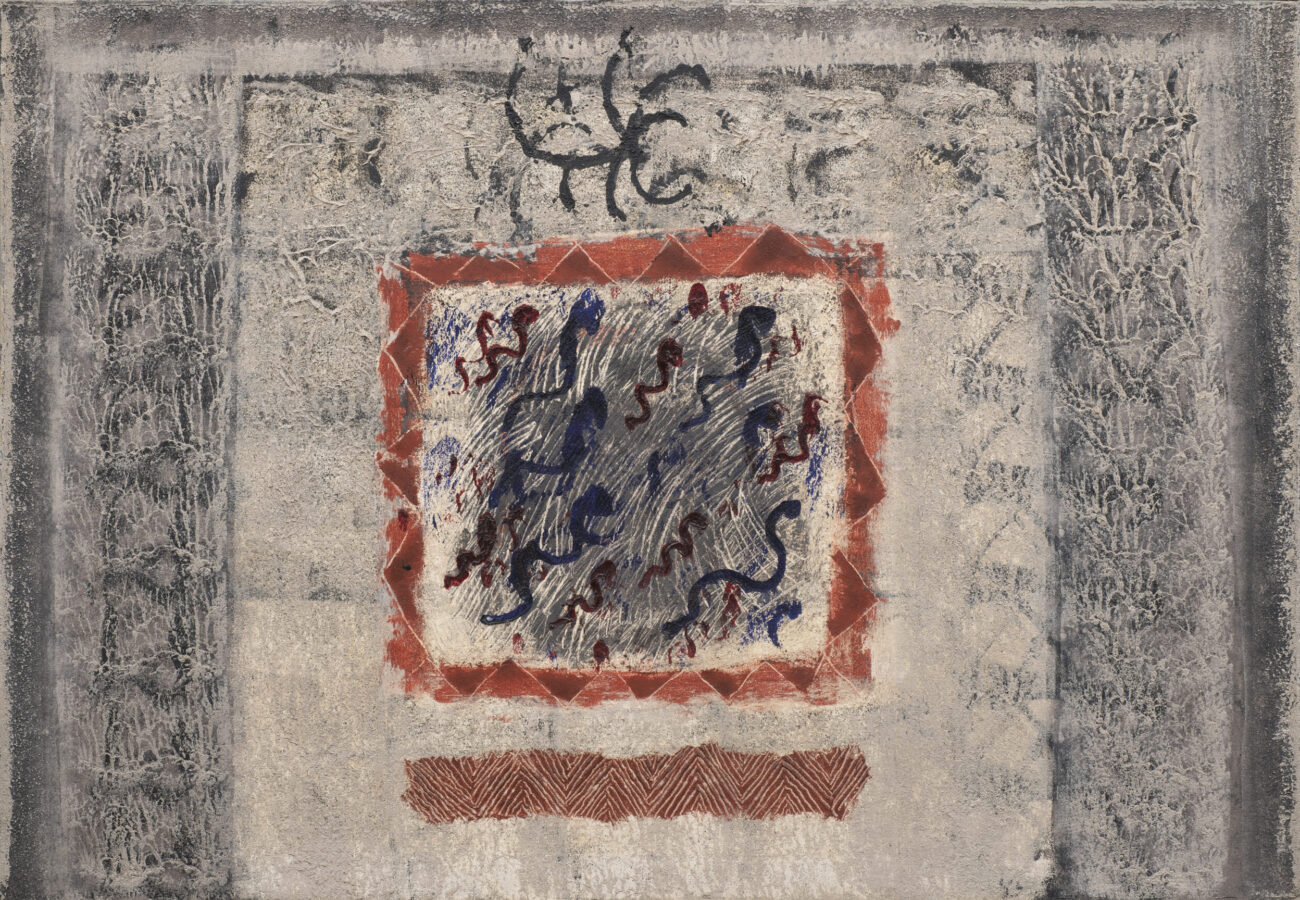

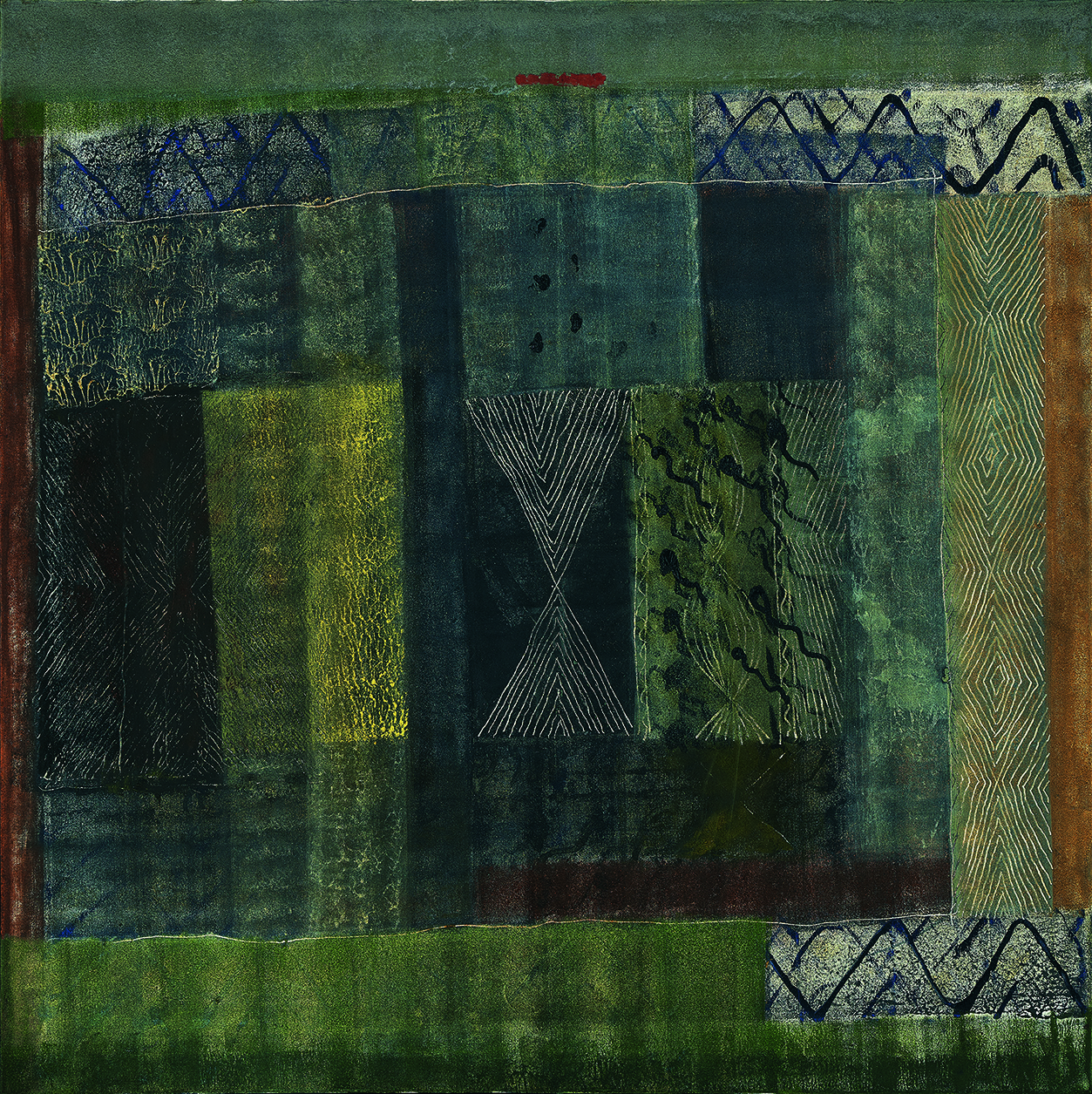

Swaminathan’s Bird, Tree, Mountain series is perhaps his most iconic body of work, one that encapsulates his synthesis of abstraction and symbolism. The paintings are composed of flat planes of color, emphasizing simplicity of form—a conscious departure from Western conventions of depth, perspective, and realism. Yet, within this simplicity lies a deep engagement with Indian folk and tribal art, creating compositions that evoke a primal connection to nature and spirituality. Pictured above Maun Gaman, or The Departure of Silence, creates an expansive, infinite reality, where mountains, trees, flowers, birds, and stones transcend their role as tangible objects. These elements, when placed in the context of his abstracted color compositions, take on psycho-symbolic meanings. The mountain, with its sense of overwhelming vastness, feels at odds with the easel’s scale, yet the bird diminishes the mountain’s grandeur. Metaphorically, the bird’s transcendence makes it loom even larger than the mountain, challenging our perceptions of scale and reality.

The critical part of the creative process for me is to drop all consciously arrived at images so that whatever else is left then comes out.

Swaminathan’s legacy is also closely tied to his efforts to elevate the status of tribal and folk art. In 1982, he founded the Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal, a multi-arts complex that became a central platform for both contemporary and traditional Indian art. Bharat Bhavan’s museum housed a significant collection of tribal art, placing it alongside modern works in a way that challenged the hierarchy between the so-called “high” art of urban centers and the “low” art of rural, indigenous communities.This approach was revolutionary in its time. Swaminathan did not view these traditions as exotic curiosities to be mined for inspiration, but as integral to India’s contemporary artistic landscape. In this, he aligns with global movements like the Négritude artists in Africa or the Mexican muralists, who sought to integrate indigenous forms into a modernist framework, creating a dialogue between past and present, local and global.

Internationally, Swaminathan’s work can be seen within the broader context of 20th-century global modernisms, where artists from colonized regions reclaimed their cultural identities while engaging with modernist idioms. His refusal to be boxed into either Western or Indian art categories has resonated with a global art world increasingly interested in decolonizing it’s canon. While Swaminathan’s work may not have achieved the global fame of contemporaries like M.F. Husain or S.H. Raza, his approach to indigenous modernism speaks powerfully to contemporary discussions around identity, heritage, and globalization in art.

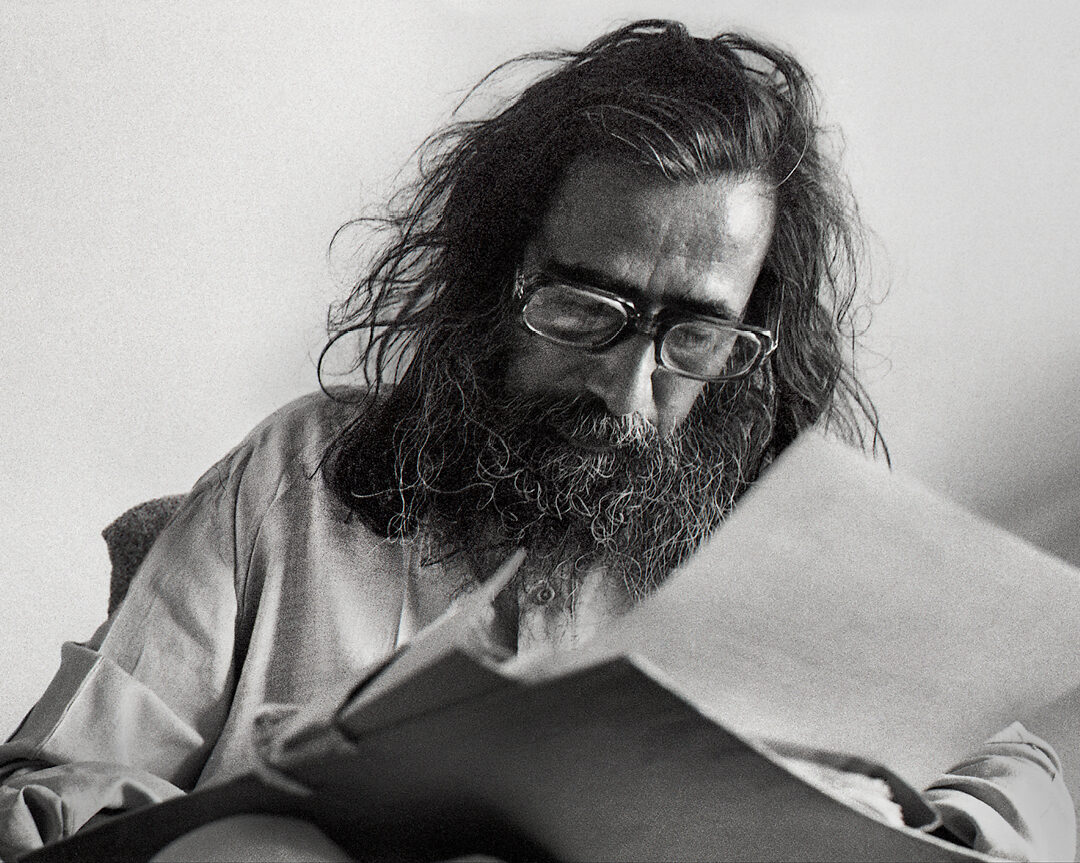

Top image: Photograph of Jagdish Swaminathan. Image courtesy of DAG Delhi.

Written and designed by Sarah Greenwood.