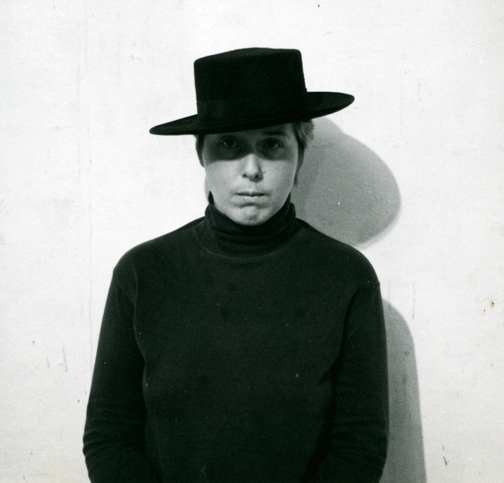

This month, Tia Collection is honored to discuss the work of Harmony Hammond, a feminist and queer artist who has influenced major aspects of the modern art world.

Born in 1944, Hammond spent her youth in Chicago, Illinois. At 17, she attended Millikin University in Decatur, Illinois where she met her husband, a fellow art student, and they married shortly thereafter. The two then moved to Minneapolis, where she received her B.A. in painting from the University of Minnesota in 1967. Hammond and her husband moved to lower Manhattan in 1969, only a few months after the Stonewall Uprising, where members of the LGBTQ+ community protested the unlawful raids by police of gay establishments. It was a time of civil rights and anti-war activism, the beginning of the feminist movement and birth of the feminist art movement. Hammond was influenced by and contributed to early feminist art projects. It was also a period of post-minimal interdisciplinary experimentation with materials and process resulting in work that was both conceptual and abstract. Feminists brought a gendered content to this way of working.

This time in Hammond’s life was pivotal. She discovered that not only was she expecting their child, but also that she no longer wished to be married. Shortly after her divorce in 1970, her daughter Tanya was born and Hammond began her role as a single mother. During her early years in New York, she worked part-time as a story-teller for the Brooklyn Public Library, and attended weekly meetings with a feminist consciousness-raising art work group that included artists Sarah Draney, Louise Fishman, Patsy Norvell and Jenny Snider and anthropologist Elizabeth Weatherford. In 1972, Hammond and Norvell went on to co-found A.I.R. (Artists in Residence), the first all-female artist-run gallery in the United States along with Howardena Pindell, Nancy Spero, Judith Bernstein and fifteen other artists. Formed at a time when it was nearly impossible for women artists to exhibit in museums and galleries, A.I.R. provided a space where they, and other women, could show their work.

By 1970, Hammond’s work had changed radically. Like many feminist artists, she abandoned the male-dominated site of painting, and instead began consciously using materials, techniques and formal strategies associated with women’s traditional arts and the art of non-western cultures precisely because of their gendered and marginalized associations and histories. Underlying this practice was the belief that materials (in Hammond’s case, fabric) and the ways they are manipulated contribute to content as much as form, sign, or symbol (what Hammond refers to as “material engagement”).

Hammond had her first solo exhibition in NYC at A.I.R. in January, 1973. The exhibition included fabric Bags which hung on the wall, the slightly larger than life sized sculptural Presences which hung out in space, drawings, and a shelf presenting small Hairbags that represented each of the women in her consciousness-raising art group, as well as baskets and sandals woven by Hammond.

The Bags and Presences made reference to women’s creative traditions such as weaving and needlework by recycling worn-out curtains, blankets, domestic linens and clothing given to her by women friends that she tore into strips, which were dipped into acrylic paint, then sewed and tied to each other.

When asked about how she conceived Bag VI, Hammond said, “At some point, I attached strips and pieces of fabric to an old bag that was lying around and realized that the bag not only functioned as an armature or ground, but as a symbol of the gendered body. I could build on it physically and conceptually. A bag is a vessel or container of sorts. A purse. A pocketbook. Women of a certain age are called “old bags”.”

She continues “Bags and Presences were about layering, connecting and building whole forms out of accumulated fragments of repurposed materials, initiating a “survivor aesthetic” that continues to inform my work to this day. They could be touched, retouched, repaired and, like women’s lives, reconfigured.” The year of her first solo exhibition also was the year Harmony came out as lesbian.

In the mid-70s, Hammond created a series of small oil and wax paintings that looked as if they were woven out of paint (as seen in Anniversary, pictured below). The surface was slowly built up with successive layers of oil paint mixed with Dorland’s wax. Braid and herringbone patterns were obsessively incised into the paint creating an irregular, lumpy and bumpy surface. Almost monochrome, up close layers of color were exposed and little points, both menacing and fragile, protruded from the surface of the painting. The “weave paintings” brought feminist content back into the abstract painting field.

Harmony Hammond, Anniversary, 1976. Oil and Dorland’s wax medium on canvas. © Harmony Hammond. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

In 1976, Hammond and Weatherford co-founded the quarterly Heresies: A Feminist Publication of Art and Politics, with a collective including, Joan Snyder, Pat Steir, Joyce Kozloff, Lucy Lippard, and others. Heresies examined the social, critical, and financial structures of the art world through a feminist lens and created a conversation around women’s historical and contemporary artistic expressions. Heresies devoted an issue to lesbian art, something that had been invisible in mainstream media and art circles. Hammond was one of the co-editors of that issue.

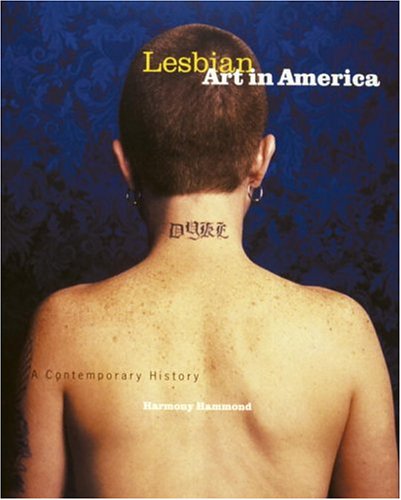

In the years that followed, feeling that there was still a lack of visibility for lesbian art and artists, Hammond curated “A Lesbian Show (1977) at 112 Greene Street, an artist-run alternative space in SoHo, and in 1990, began work on Lesbian Art in America: A Contemporary History, which took over a decade to write (Rizzoli, 2000). In the book she wrote, “We cannot afford to be silent or to let others decide what kind of art we may or may not make, nor let our creative work be ignored, ‘straightened,’ de-historicized, decontextualized, or erased.” To this day, twenty-two years after publication, Lesbian Art in America, remains the primary text on the subject.

“The women’s movement changed my life—and my art” .

Harmony Hammond, Inappropriate Longings, 1992, oil, acrylic, canvas, linoleum, latex rubber, metal gutter and water trough, dry leaves, triptych. Jeffrey Sturges/ ©2018 Harmony Hammond, Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY/Courtesy the artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York.

In 1984, Hammond, her partner and daughter moved to New Mexico. Her work then and throughout the 90s’ responded to the new physical and cultural landscape. Still working with found and repurposed materials (now straw, fabric, linoleum, hair, burnt wood, rope, gutters, screens and rusty corrugated roofing tin she collected on her way to and from Tucson where she taught at the University of Arizona (1989 – 2005), combined or juxtaposed with traditional art materials such as oil paint, canvas and latex rubber, Hammond created mixed-media installational paintings such as the triptych Inappropriate Longings, (1992) dealing with loss, violence and survival.

In the left-hand panel of Inappropriate Longings (1992), the words “GODDAMN DYKE” are incised in gold-colored latex next to fragments of floral-patterned linoleum. A bleeding linoleum house-form occupies the center panel, and the right hand panel is covered with the under-dark-side of torn fragments of linoleum, upon which hangs a metal gutter suggestive of the female body. A human-size metal water trough full of dry leaves sits in front of the painting, signifying loss of life fluids. Taken together, these elements insert a lesbian presence into regions of rural America and the modernist painting field.

Over time, the mixed-media paintings got simpler as Hammond tried to get meaning into the paint itself and it’s application. “Hammond has always shown a commitment to challenging the history of abstraction—and queering it,” said Alexander Gray, whose gallery represents her. “She does that with her materials, with imagery of scarring, sutures, wounds, orifices, seepage, leakage. She pushes against abstraction in the Malevich mold as a pure space, a spiritual, otherworldly device.”

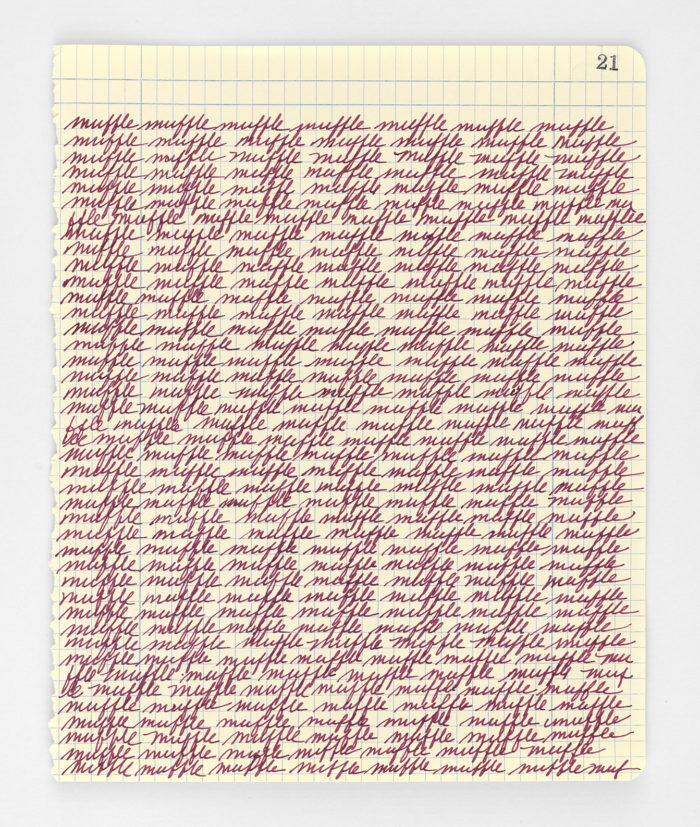

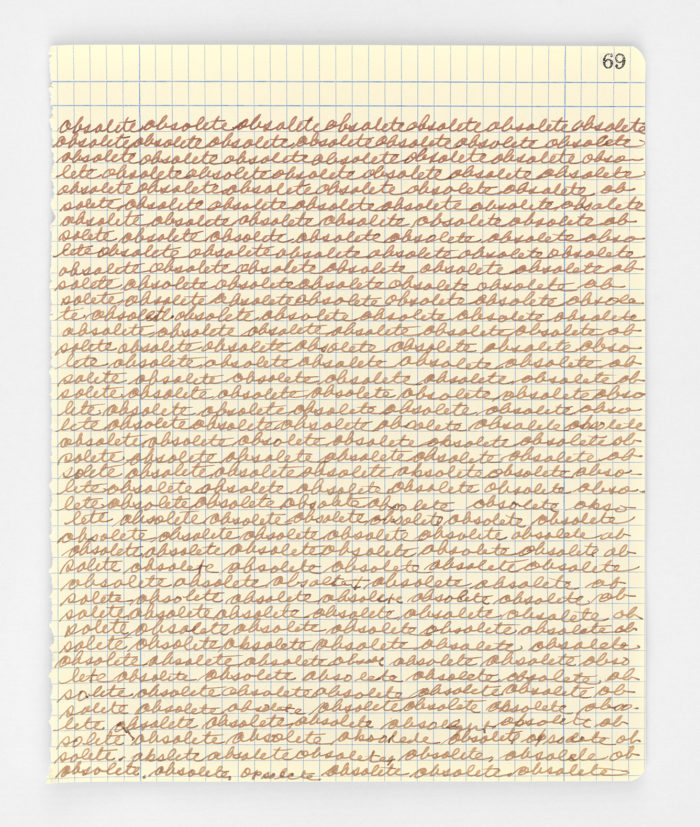

For the last 20 years or so, Hammond has made large, thickly painted near-monochrome paintings that continue to bring content to the abstract painting field. She describes these paintings as “more condensed, with fewer and more selective materials in any given piece, and therefore, less narrative”. Incorporating recycled burlap, other fabrics and metal grommets, the layered surfaces are variously pieced, patched, or wrapped, suggesting the body and binding, bandaging, bondage, restraint and constraint – possibilities of connecting, tying down, securing, reinforcing, embracing but also healing. Underlayers of color representing those who have been muffled, silenced or erased, ooze out through cracks, crevices, seams, flaps and grommeted holes in the painting surface. .” As Hammond says, “the paintings are about giving voice and agency. It’s like they are “unbecoming” monochrome”.

A special thank you to Harmony Hammond for the recognition for ALL artists, as well as to Alexander Gray Associates for sharing their insight and high resolution images. ART©HarmonyHammond/

Written and designed by Sarah Greenwood.