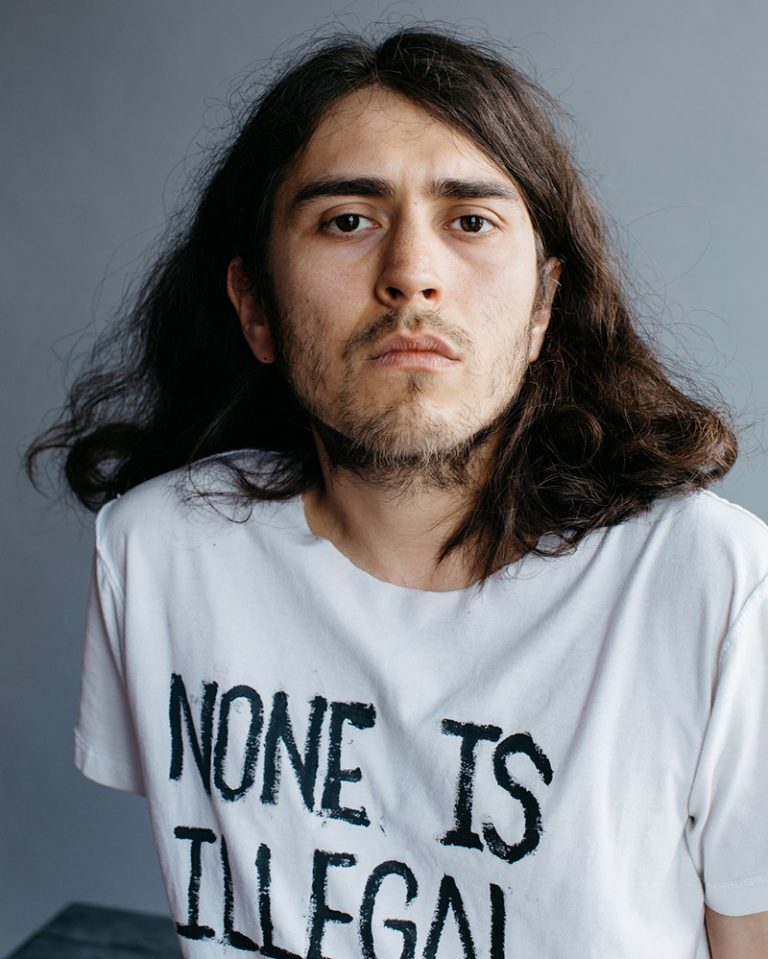

Born on the U.S – Mexican border in San Ysidro, California, Esteban Cabeza de Baca’s parents were very politically active, taking part in the Brown Berets, Black Panthers, Chicano and Native American movements. While having a conversation with the blog “Two Coats of Paint”, he described what is was like growing up,“People would run through our backyard and steal clothes; helicopters would pass and wake us up. My parents would also house so-called illegal immigrants in our basement. So, I grew up with the idea of giving sanctuary to people who are designated illegal.” Esteban’s family ancestry is complex, tracing a direct link to the Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, someone who advocated for a grand alliance with Indigenous peoples. As Native American and Mexican, Esteban draws from his ancestors and from his upbringing for themes and inspirations.

Esteban Cabeza de Baca, Cieneguilla Caves, 2019

“I want history to spill out in front of the viewer and get them to think about our story living with Earth.”

Using many techniques, including layers of graffiti, mixed with elements inspired by the landscape and pre-Columbian pictographs, Esteban takes the viewer beyond a single plane and it’s easy to mistake his paintings as three-dimensional. Nepantla, the term coined by Chicana cultural theorist Gloria Anzaldua, describes the “in-between situation” and is one that strongly resonates with him. The concept of Nepantla describes how the Aztecs were a modern civilization with their own complex social structure and were being colonized by the Spanish at the same time. For Esteban, embracing all parts of his ancestry that were shamed out of his ancestors in the past is the goal of his artistic practice. When creating the body of work inspired by New Mexico, a state very familiar with the complexity of Native American and Spanish history, Esteban said “I counter the colonial perception of America by acknowledging who we were before 1492 by going to the cave paintings at Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico. When I’m there, I recognize I’m standing in an ancient American painting studio.”

Esteban Cabeza de Baca, Moon Window, 2018

Featured in Vogue this past fall, Esteban spoke about plein air painting, “As a kid, I would paint in the backyard of my great-grandma Bonita’s farm. I love painting from nature because, if we listen, it teaches us the best way to live… what America would look like without borders; but reality is so much more interesting than fictional painting in a studio. Plein air painting helps me talk to my ancestors, but also shows me how to really listen to the land.”

Esteban Cabeza de Baca, Ghost Canyon, 2019

Beyond connecting with the land, Esteban wants to reach out to others, teaching them about our history with the earth and the history of landscape painting. White European painters have depicted the American West for hundreds of years and, while their landscape paintings are beautiful, they have a dark element to them. These images of the land often represented the early/mid-19th century idea of Manifest Destiny – the belief that the land was god given and theirs to take. However, that land was already under the care of others who had long been its protector. Esteban’s landscapes break that tradition by bringing abstract strokes into the composition, disrupting the idyllic image. It’s his way of reclaiming the land, acknowledging the pain behind colonization and the loss it continues to inflict. In the fall 2019 newsletter for his alma mater, Columbia University, Esteban stated, “Getting people to see the complex layers to not only the history of landscape painting, but also of America before 1492, makes me optimistic about the future. I want to be a bridge between communities.”

Esteban’s work, with its incredible meaning, has been displayed around the world. Despite the fact that he is only in his thirties, he has participated in many residencies worldwide- Byrdcliffe Residency in Woodstock, NY; Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program in Brooklyn; LMCC Workspace Program iand The Drawing Center Open Sessions n New York; The Rijksakademie in Amsterdam; Carrizozo artist-in-residence in Carrizozo, NM; Artist in Residence at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville; and, most recently, Atlantic Center for the Arts in New Smyrna Beach, Florida.

His solo exhibition Let Earth Breathe opened in April, 2022 at The Momentary in Bentonville, Arkansas, while other works can be viewed at Harvard University in Cambridge, MA, as well as the Denver Art Museum, CO.

Written and designed by Sarah Greenwood.