Edmund de Waal has been a maker for most of his life, throwing pottery and ceramics on the same back-breaking stool he has had for the past three decades in his south London studio. He first began making pottery at the age of five, a childhood interest that gave way to an over-50-year dedication to the craft. At 17, he began an apprenticeship with Geoffrey Whiting, a student of Bernard Leach, who is considered the “father of British studio pottery.” His later encounters with porcelain led to a postgraduate diploma in Japanese and a year at the Mejiro Ceramics Studio in Tokyo.

While in Japan, de Waal also worked on a monograph of Bernard Leach, researching Leach’s papers and journals in the archive room of the Japanese Folk Crafts Museum. In 1997, he published his first book, Bernard Leach (St. Ives Artists), which presented an objective yet critical look into his former instructor’s teaching and practice. This project prompted a new trajectory for de Waal, as he began to make a series of porcelain jars with impressions, which reflect the hand of the maker as well as a sense of the passage of time, arranged in groups and sequences.

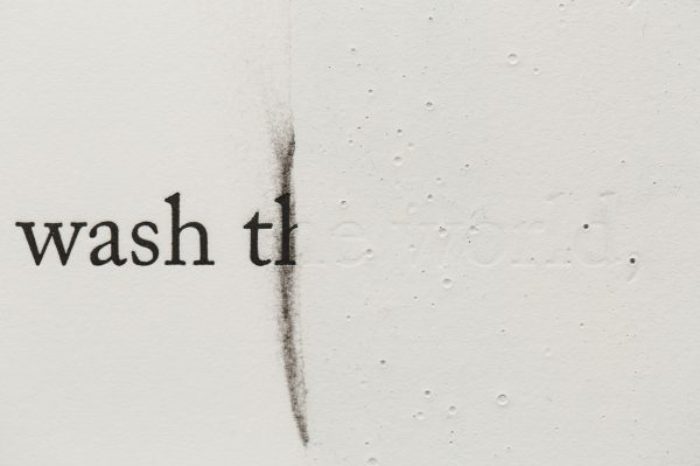

During this creative process, de Waal also began a deep investigation into the origin and reason for creation, which has naturally led him to become a contributing resource to the pottery world, having written or assisted with over eight books about ceramics and its history, including his critically acclaimed memoir, The Hare With Amber Eyes. In this book, de Waal chronicles the history of his family and their collection of Japanese netsuke, tiny carved sculptures, that were passed down from generation to generation, were lost and then miraculously returned to his Austrian family following Nazi persecution and displacement during the Second World War. This led de Waal to a deeper appreciation for the power of objects and the stories they hold, themes which he then explored in his own practice. Often simple and unadorned, yet deeply compelling, de Waal’s objects are imbued with meaning, as if the artist is writing a story in clay. Unassuming forms, such as cups and bowls, not only hold memory and emotions in de Waal’s hands, but also symbolic meaning, stemming from their long history in the practice of pottery.

In Feng Shui teachings, a cup can represent both nourishment and ritual, while a bowl can represent abundance and community. Rooted in this belief that objects are more than they appear, de Waal also explores the meaning behind colors in his pottery groupings. He often employs a muted palette of whites, blacks, and celadons, which evoke a sense of calm and serenity in the viewer, as well as awareness of place and time.

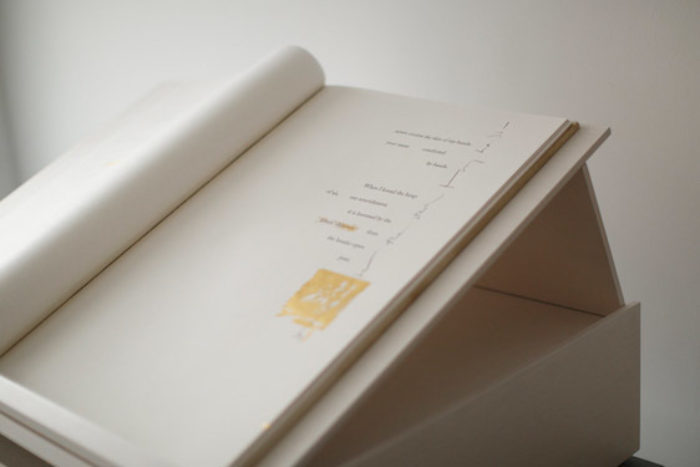

His work psalm, first shown in Venice in 2019, consists of 133 porcelain vessels arranged in four large scale vitrines; their arrangements echoing the first ever printing of the Talmud by Daniel Bomberg, printed in Venice in the early sixteenth century.

The use of porcelain, which is both fragile and enduring, speaks to the idea of memory as a fragile yet persistent force. Overall, de Waal’s pottery groupings and meanings are a testament to the power of objects—connecting us to our past, to our emotions, and to each other. Through his work, he invites us to contemplate the stories that objects can tell and to appreciate the beauty and complexity of the world around us.

Edmund de Waal has helped to reinvigorate the art of ceramics, bringing new attention and appreciation to this media. De Waal’s ceramic sculptures and installations have been exhibited in museums and galleries around the world, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Gagosian in New York, and the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. In recognition of his achievements, de Waal has been awarded numerous honors, including a CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in 2021 for his services to art.

Written and designed by Sarah Greenwood.