In celebration of artist Bertina Lopes and the inclusion of her mixed media work Rais Antica 2 – Una Historia Verdadeira in the 2024 Venice Biennale, courtesy Tia Collection, we are honored to highlight her dedication to political activism and social criticism.

Born 1924 in Maputo, Mozambique, Bertina Lopes moved to Lisbon at a young age, where she received an arts education. There she was inspired by the avant-garde painters of Portuguese Modernism, in addition to other artistic international movements. Lopes became an influential professor upon her return in 1953 to Maputo, where she engaged with the country’s poets, writers and political activists. Mozambique had become an overseas province to Portugal, attracting thousands of Portuguese settlers to the country as the economy expanded rapidly. Much of Lopes’ body of work during this time reflected not only African iconography, but also the political events of the time. Bertina was forced to return to Portugal in 1961 as a result of the tumultuous political unrest between the two countries. Prosecuted by the Portuguese International and State Defense Police (PIDE), Lopes fled to Rome, where she remained for the rest of her life and where the subject of African identity took on an even more compelling meaning for the artist, expressing an end to colonialism and a desire for independence.

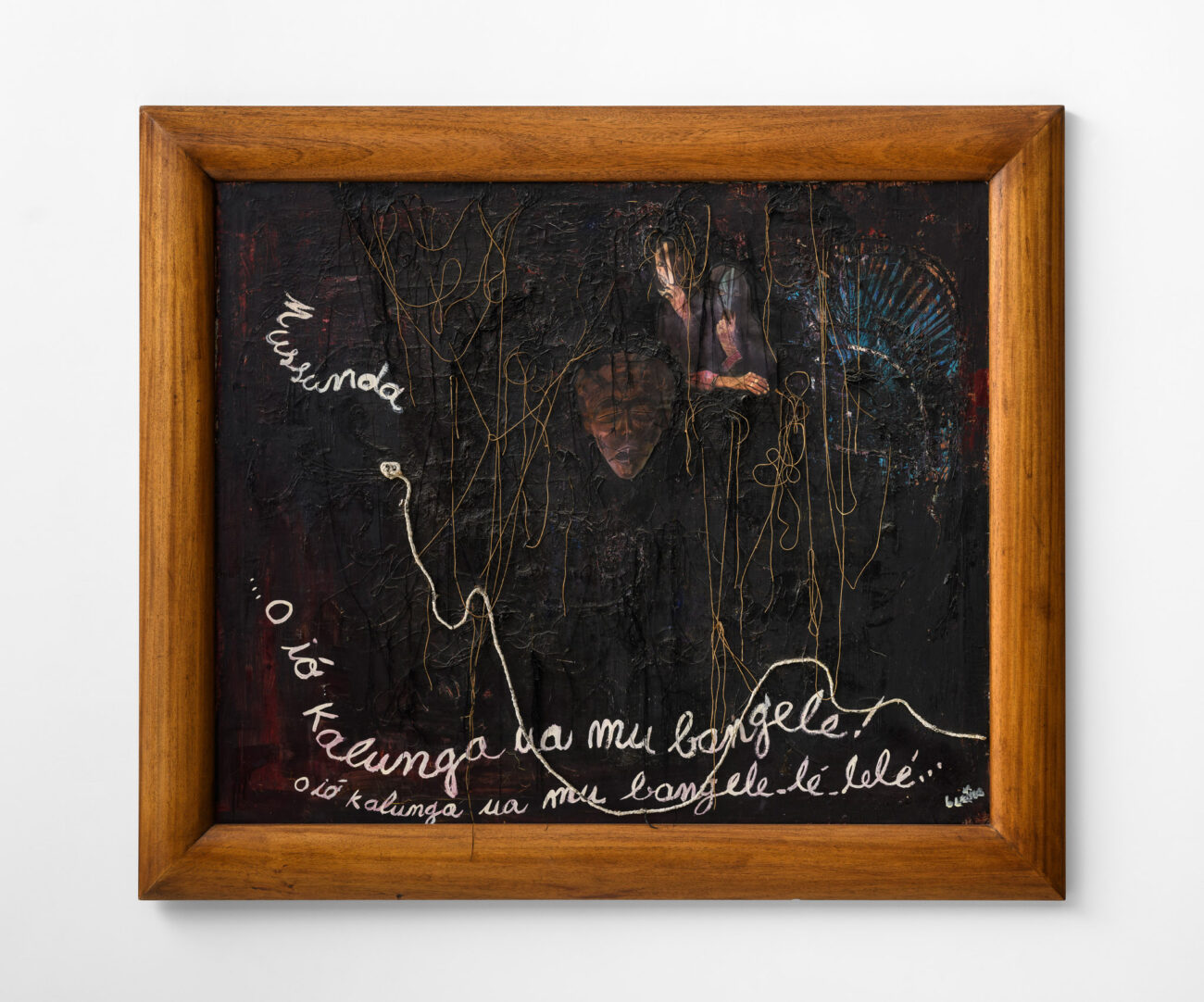

In 1961, the same year that the Portuguese Colonial War started in Angola, poet and eventual first President of Angola Agostino Neto wrote his revolutionary poem which acted as a rallying cry and was dedicated to the Mussunda region of Angola. Lopes, a friend of Neto, was inspired by his political work, and created Mussunda (dedicato al Agostino Neto) as an homage and memorial to the massacres that ensued. The central collaged image is of a classic Chokwe mask (a genre that honors female ancestors as they trace their descent through matrilineality). Chokwe masks were often worn in celebrations to mark initiation into adulthood, dissolving the bond between mothers and sons, much like the dissolution of the bonds between the colonial powers and the native peoples of Angola. The two figures in Lopes’ work each hold such a mask in front of their face. This work also shows the importance of friends and fellow artists to the artist, and the influence of the wider political network surrounding her.

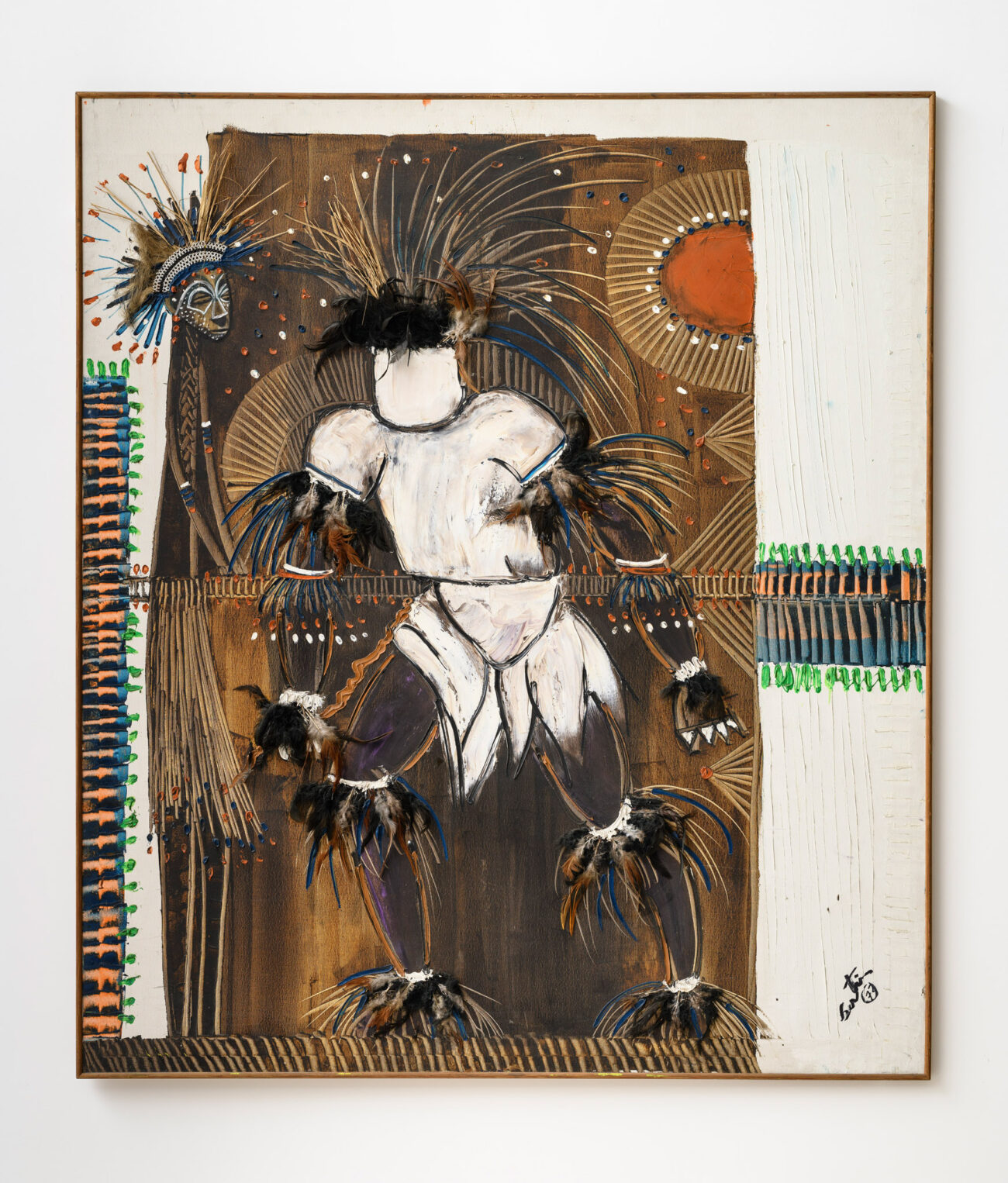

In the early 1960s, Lopes began working on her Rais Antica series, which played upon the Western visual art’s widespread trend of consuming and incorporating what was then termed as “primitivism” or “tribal” forms, borrowed from African and Oceania art. After acquiring a work from this series, the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art wrote how “Lopes references the traditional methods of economy and production in Mozambique (palm fibre) – the ‘ancient root’ of the country and hence the series of painting’s title.” Incorporating feathers, reeds and thickly painted impasto in Rais Antica 2 – Una Historia Verdadeira, the central male figure is indeed a force, carrying within him the kernel of Lopes’ intent around so-called “Primitivism.” For Lopes, such a “root” was the very essence of its history, its people—for her, everything.

It’s also interesting to note that Lopes depicts a local tribesman as the “warrior” here, as the Portuguese were under increasing pressure to recruit local tribesman for their Flechas (Arrows) units—units specializing in reconnaissance and tracking, considered better suited to try and create relationships with the local populace (similar to the “hearts and minds” strategy used by the US in Vietnam). By introducing the Chokwe mask, Lopes makes it clear that the local tribesmen are under the rule and ancestral obligation of the Mozambican people—not the Portuguese. The political situation in Mozambique runs parallel to the subject matter of her paintings and so here, painted in 1972, Lopes was inspired by the infamous massacre of Wiriyamu that year, in which nearly 400 civilians were killed by Portuguese soldiers.

Omaggio per la morte di Picasso (Homage for the death of Picasso) is an homage to Picasso’s Guernica, which was hugely influential on Lopes’ practice. Lopes was introduced to Picasso through the Spanish gallerist Juana MordòIt. Their brief meeting would leave an indelible mark on her memory; Omaggio per la morte di Picasso was painted in 1974, following another brief yet intense meeting with the master, just a few months before his death, and the same year a ceasefire was negotiated, with Mozambique’s final independence in 1975. Like Guernica, it shows the tragedies of war and the suffering it inflicts on individuals: specifically, the 10-year War of Independence in Mozambique and its impact on the local people. She features tormented figures with their hands lifted up and mouths stretched wide open in pain. Unlike Picasso, who didn’t feature any soldiers in his painting, she paints the figures of two Portuguese soldiers, each wearing a helmet with a gun slung across their shoulder. Four doves are featured in the painting, a direct allusion to ensuing peace with the signing of the ceasefire. The antiwar painting is an explicit critique of the Portuguese colonial powers, and a reminder of the suffering endured by the Mozambicans.

Other works by Lopes during this decade through the late 1980s further signify the grave economic and military problems of Mozambique’s victory for independence, as well as the subsequent civil war which ended in 1992. From the late 1990s to the 2000s, her practice denoted a freedom of gestural abstraction and extraordinary color, often made with industrial paints. In addition to participating in the Venice Biennale twice, Lopes achieved significant cultural recognition and won numerous awards and prizes. Bertina Lopes passed away in Rome in 2012.

Tia Collection gives special thanks to author and art historian Claudio Crescentini for his important work around the lids and legacy of Bertina Lopes.

Written and designed by Sarah Greenwood.