Contemporary artists Anthony Akinbola, Helena Foster and Ozioma Onuzulike blend their Nigerian backgrounds and histories with modern and conceptual practices to create works of redefining resonance. Addressing the complexities of both post-colonial life and their current communities, each artist welds and empowers their unique vantage point within their chosen mediums.

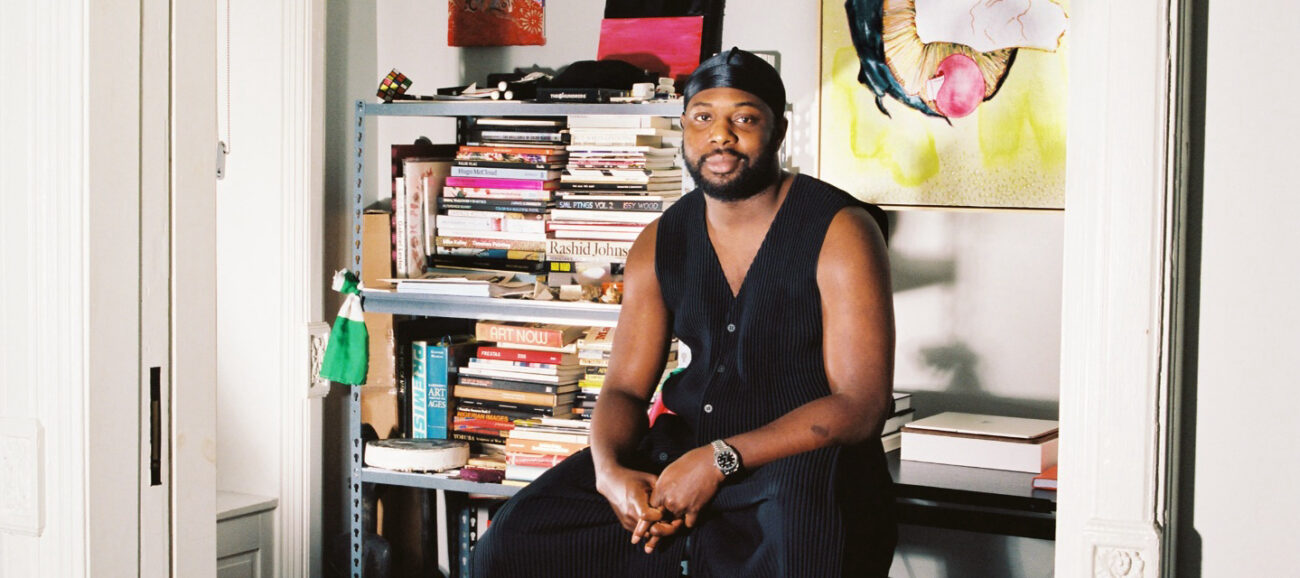

Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola (b. 1991, Columbia, Missouri, USA) is a first-generation Nigerian-American raised between Missouri and Nigeria, and currently based in Brooklyn, New York. Foregoing conventional approaches to painting and sculpture, Akinbola reimagines identity construction through the use of the readymade in his conceptual art practice. Through the use of totemic materials like palm oil, hair brushes, and pomade—elements integral to Black hair care—Akinbola investigates the challenges within and facing the Black community. While the recognized readymades are in part a celebration of everyday Black life, Akinbola grapples with the commercialization and fetishization of Black culture.

In his ongoing series of Camouflage paintings, Akinbola utilizes the du-rag, a satiny cloth cap worn tautly over the head in Black culture. Many of his “Camouflage” paintings feature monochromatic palettes, with compositions rendered entirely in shades of red, yellow, black or blue. Yet closer inspection reveals subtle differences in hue and texture, as Akinbola sources his material across multiple Black beauty suppliers. The variated colors in sheen and shadow achieve a complex study in color through each single or multi-paneled work. In an interview with Zoë Hopkins (via Artsy), he describes how he conceptualizes these works as a form of what he terms representational abstraction: “I realized I could use this material because it’s so politically and culturally loaded,” Akinbola said. “But they also give me a whole range of colors to work with, and a formal vocabulary too. They exist in that sweet spot between something that is totally abstract, but also representational.”

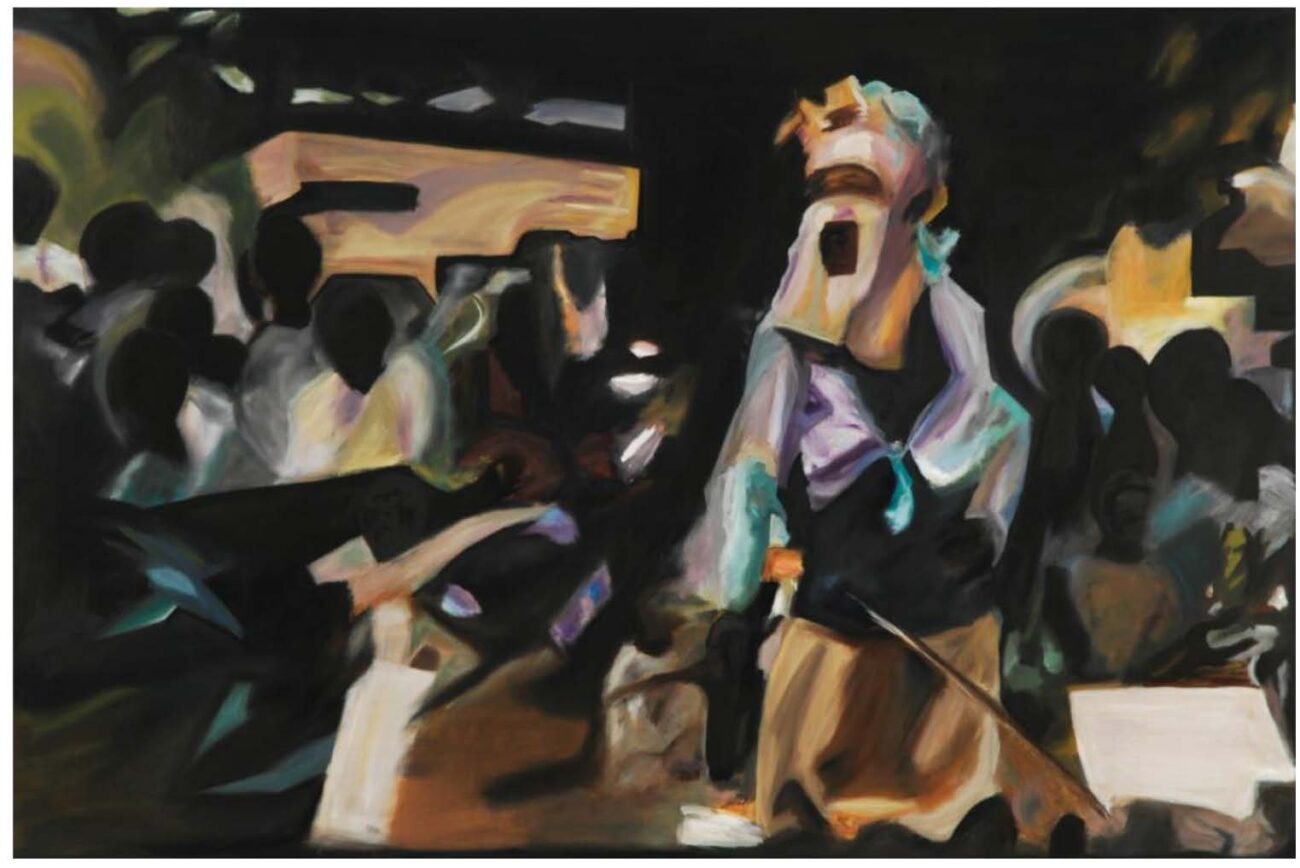

Helena Foster (b. 1988, Benin City, Nigeria) seeks to better understand her Nigerian and British heritage through her painting practice. Raised in Nigeria and now working and living in London, Foster mingles childhood memories and experiences with present-day complexities and cultures. The dream-like characters and imaginary places of Foster’s paintings range from depictions of daily life to the mystical. Foster’s rich use of color and layering of paint intensifies her subjects and scenes, often causing figures to blend into or become framed by their surroundings.

Lagbaja I (pictured below) depicts the Nigerian Afrobeat musician Lagbaia, known for his unique style and masked persona. Emerging in the 1990s, Lagbaja blends traditional African rhythms with modern influences. His name, meaning “anonymous” or “nobody” in Yoruba, reflects his commitment to representing the common man. By wearing a mask, Lagbaja emphasizes the collective identity over individual fame. In addition to capturing the energy of Lagbaja’s performances, Foster’s paintings also explore the complex layers of meaning that his work embodies, such as gender, sexuality and social justice. Foster’s own paintings mirror these themes, and offer a unique perspective on the experience of being an outsider. Lagbaja I is a potent reinforcement of the power of art and self-expression in challenging the status quo.

Ozioma Onuzulike (b. 1972, Achi, Nigeria) is a Nigerian artist, poet and African art and design historian. His compelling and contextually complex sculptures and installations often incorporate found objects and materials, and explore identity, memory and societal issues. Like Foster, Ozioma also finds inspiration in the mask, or Lagbaja. Lagbaja’s Extra-Large Danshiki (pictured below) belongs to Ozioma’s Palm Kernel Shell Beads series, wherein he reflects on beads’ historical role as commodities for slave trade in Africa by European merchants. Ozioma subtly references various goods traded during that era—spices, silk, gunpowder, jewels, textiles, glass, wine, and mirrors—through nuanced colors, textures and formal structures. Here, the mask explores the aesthetics of social change, focusing on Africa’s shift towards the cultural legacy and resilience embodied in these textiles.

As the demand for human cargo grew, beads became scarcer, increasing their value and production. Following the abolition of the slave trade, merchants turned to Africa’s minerals and agricultural resources, such as palm oil and palm kernels. In this series, Ozioma transforms palm kernel shells into contemporary currency, replacing the beads of the slave trade. Using local clays, he crafts these beads and embellishes them with recycled glass and ash glazes. Ozioma incorporates these new beads into textile-like structures, reminiscent not of the slave trade era but of Africa’s prestigious cloths like the Igbo’s Akwaete (a woven textile from the Abia state of Nigeria), Ghana’s Kente (basket woven designed textile) and the Yoruba’s Aso-Oke (a woven cloth often used for formal garments in the region). Through his ceramic works, he highlights these textiles’ rich history within West African weaving traditions and their cultural and political significance.

Written and designed by Sarah Greenwood.