For this introductory discussion, I have four artists out of the larger group that will be joining the Tia Collection which shows the broad range and creativity that Indian folk and tribal artists possess. Three of these gifted artists were discovered in the early eighties when J.Swaminathan, one of India’s greatest contemporary artists, as well as a scholar and visionary, was director of the Bharat Bhavan, a ground-breaking institution for folk and tribal art set up in Bhopal, the capital of the state of Madhya Pradesh in the center of India. He believed strongly that there was an incredible reservoir of talent lying within the folk and tribal communities of the state so he sent out teams of young, dedicated scholars and artists to search for them and the impact of those early expeditions resonates until today.

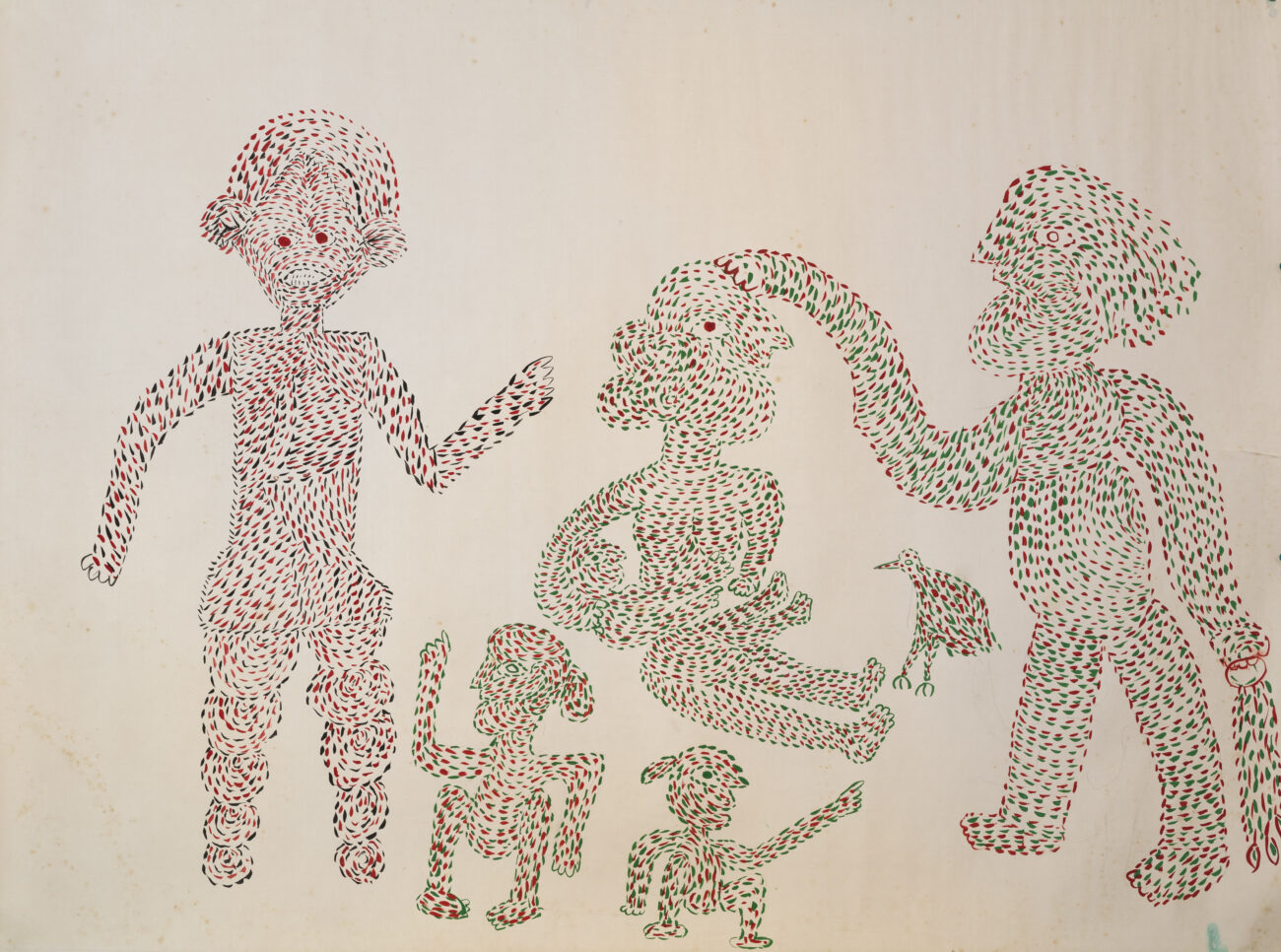

Belgur Maravi was one of the many brilliant tribal artists that Swaminathan’s team discovered in the early eighties in the far eastern part of Madhya Pradesh which was incorporated into a new state called Chhatisgarh in 2000. The rare early work by Belgur Maravi below was created around 1985 and has a vivid pointillist in style so characteristic of the region’s art, architecture, and body ornament. It depicts the moment when a young woman has been brought before the village medicine man to be exorcised while her husband and children look on. It’s a powerful composition that reveals a rare and intimate glimpse into tribal life and ritual. Belgur was never able to fulfill his potential as an artist probably because he lived so far away from Bhopal and the main art markets. However, we have recently rediscovered him still living in his ancestral village and, at the age of sixty-five, he has again decided to take up painting seriously. His latest work, still rooted in the pointillism of his youth, now exhibits a dynamic and mature talent that will bear watching over the coming years.

The second artist is Bhuri Bai, who belongs to the Bhil tribe, the largest tribal community in the country, which spreads across central and western India. Her precocious talent was also discovered in the mid-eighties when she was working as a daily laborer at Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal. Her first introduction to art is now something of a legend. Swaminathan, the director, asked her and her friend, Lado Bai if they could paint. They replied frankly that they didn’t know so he gave them paint, paper, and brushes and they never looked back. Both are now recognized as the two greatest masters of Bhil art. One of the rarest of her early works from around 1985, The Forbidden Forest, portrays a dream world where colorful aquatic and land creatures float in space above an arcane ritual enacted under the shade of a pink palm tree. Bhuri Bai, now in her late fifties, still lives and paints in Bhopal and was awarded the Padma Shri in 2021, one of the nation’s highest awards for a distinguished and lifetime contribution to art and culture.

The fourth artist propels us into the present. Jodhaiya Bai Baiga is a tribal artist who was discovered in 2008 at the age of sixty-seven by Ashish Swami, a contemporary artist and an accomplished teacher, who had set up an art studio dedicated to the revival of folk and tribal art in the small village of Lorha near the town of Umaria in eastern Madhya Pradesh, the heartland of tribal India. Paper, brushes and paint were all free to use for anyone who wanted to try their hand at art. After some hesitation, Jodhaiya Bai decided to join the classes and Ashish realized from the outset that she had an exceptional talent. When interviewed recently, Jodhaiya Bai recalled her first experiments with art. “When I learned about a teacher who was willing to teach for free in our village, I decided to give painting a try, something I was never interested in. Yet, on the very first day, I found my passion. Painting takes me to another world where I am as free as a bird.”

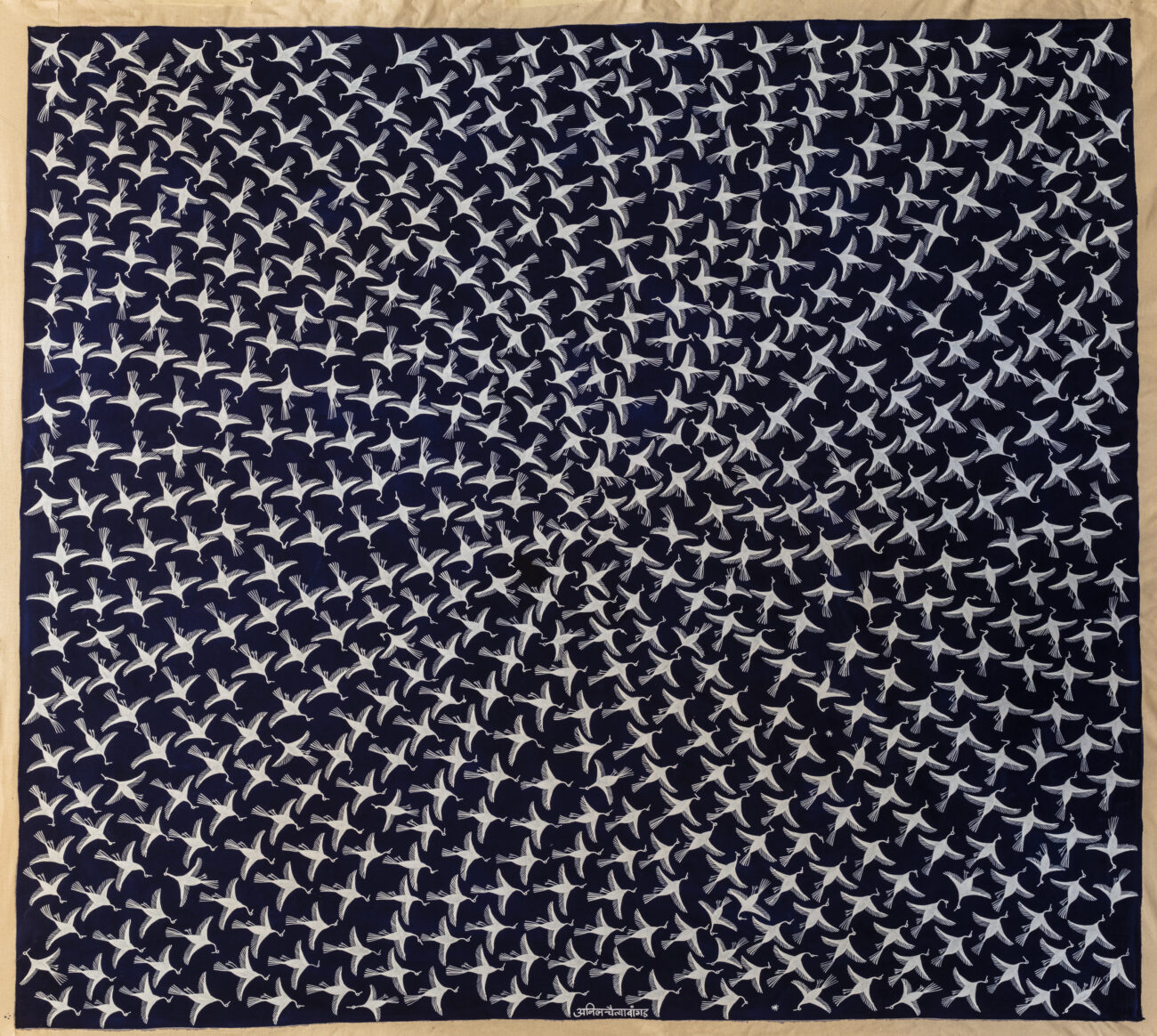

Now in her early eighties, Jodhaiya Bai loves to paint the trees, birds, and creatures of the nearby Bandhavgarh forest reserve as well as the gods and goddesses of the Baiga tribal pantheon. A bit temperamental at times, she never hesitates to tell you exactly what she is in the mood to paint and also likes to imbibe now and then. I still remember when she whispered in my ear, her eyes twinkling, that she had heard somewhere that rum is good for health. Her work continues to exhibit a masterful artistic vision, very much her own, which is amazing considering the Baiga tribe did not have strong artistic traditions from which she could draw. One of her largest and most compelling recent paintings which is joining the Tia Collection is The Burning of Bandhavgarh Forest which shows her beloved forest on fire with the faces of the creatures and birds traumatized in fear as flames engulf their world. In March 2022, Jodhaiya Bai received the Nari Shakti Puraskar for women’s empowerment and was then awarded the Padma Shri in March 2023, the highest civilian honor for cultural and artistic achievement by the President of India. She was the first of her tribe to receive this prestigious award and it has encouraged many tribal girls and women across the country to explore the world of art.