Tia Collection is broad in its areas of collecting interest and fortunate to consider and acquire works of art directly from artists and other private collectors, as well as working with galleries around the world and auction houses. One aspect of collecting art is sharing stories about the artists and the works they create and the impression the work makes within each of us.

As 2024 comes to an end, we wanted to take a moment to narrow our focus on several impactful works that have become part of the collection. We continue to recognize the accomplishments of well known artists, as well as emerging storytellers and this focused selection exemplifies the diversity of our collection.

Rob Dean, Asian Curator

Earlier this year, I was delighted that Tia Collection expanded upon its body of Mid-Century Modern Indian sculptures by acquiring Surya Dev by Adi Davierwalla. This is certainly an important highlight of this year’s acquisitions in Indian art for the collection. Davierwalla was not a trained artist, but a pharmaceutical chemist by profession. When he started creating sculptures around 1953, his works were unlike anything ever seen before in India. His aesthetic choices reflected a unique great clarity of thought. Davierwalla worked in several mediums over the course of his short, but highly productive career, choosing between wood, marble, steel, aluminum, and stone. He moved effortlessly between large, outdoor welded metal abstract compositions, and sensitively rendered, smaller, carved wood figures.

Surya Dev (or Sun God), made in steel and dated 1967, was created by Adi Davierwalla as a study for a public sculpture of the same name, that was commissioned for the Ananta Co-operative Housing Society in Mumbai. The full-size version of Surya Dev stood at a monumental twelve feet tall, but, unfortunately, has now been demolished. A comparison between the maquette and photographs of the monumental version reveals minor differences between the two sculptures. However, despite these minor changes in form, the maquette reflects the iconic presence that is witnessed in the final version. Furthermore, the comparison provides vital information about the conceptual evolution that occurred between the initial germination of the artistic idea for the sculpture, and its completed form. Religious subjects of both Christian and Hindu themes remained a constant throughout his career, but were tackled in different mediums and forms at different stages of his career. Although the current figure is named after the Hindu solar deity, Surya, its treatment in artistic terms does not follow classical Indian sculptural traditions or classical iconography. Instead, the form falls somewhere between the contemporary tribal sculptural tradition of India and the Post-Industrial sculptures of the West.

In the death of Adi Davierwalla, contemporary art has lost a sculptor with a clear mind and a modern sensibility. His work is the work of a pioneer, who went forward, free from the trammels of the past.

Karon Hepburn, European Curator

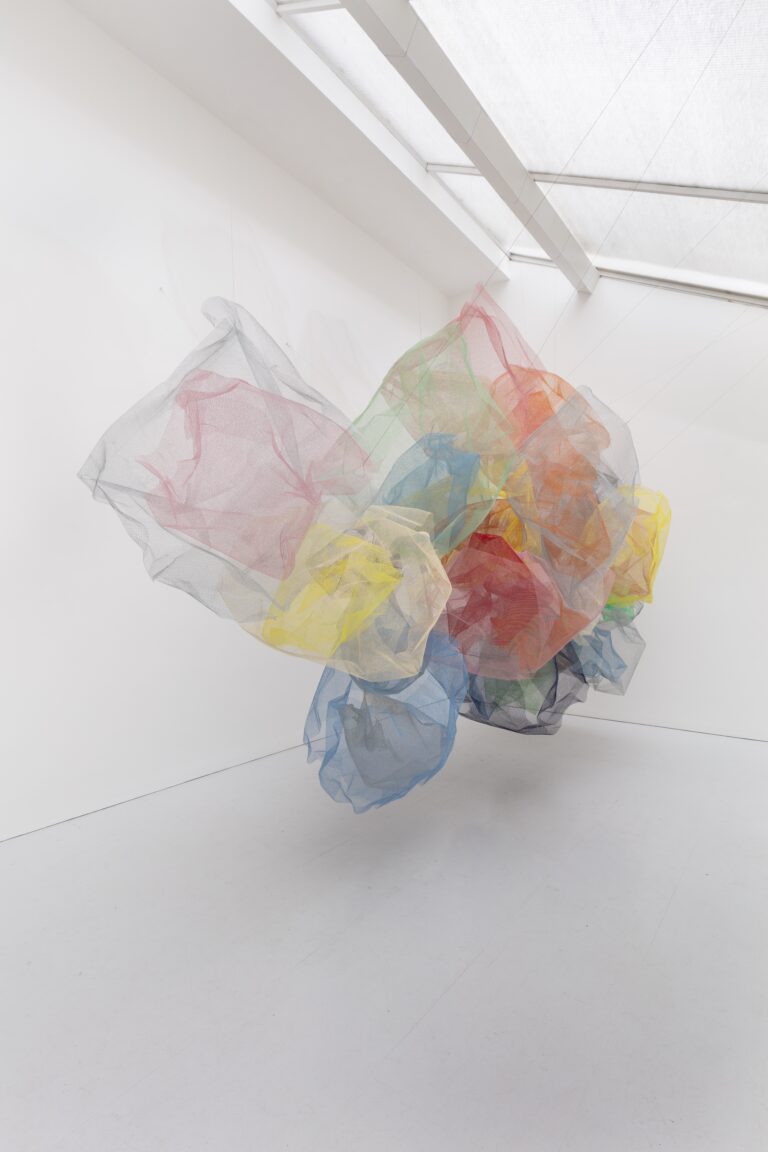

Rana Begum, born in Bangladesh and living in London, UK, is known for her captivating exploration of light, color, and form, often achieved through geometric abstraction. Her mesh artworks exemplify this approach, as they blur the boundaries between sculpture, painting, and architecture. These works are influenced by her upbringing in Bangladesh, where she was exposed to Islamic art and architecture, and by her fascination with the interplay of light and shadow in urban environments.

Begum’s mesh pieces typically consist of industrial materials such as perforated steel or aluminum, painted in vivid colors, or left bare, to reflect their surroundings. These works transform, depending on the viewer’s position and the ambient lighting, creating a dynamic, ever-changing experience. The interplay between solid structure and ephemeral light evokes both permanence and transience, inviting viewers to reflect on the fluid nature of perception. Her art bears the influence of minimalism, echoing the work of artists like Donald Judd and Agnes Martin, yet it is deeply rooted in her cultural heritage. The repetition and symmetry in her designs parallel the intricate patterns found in Islamic art, offering a modern reinterpretation of traditional motifs. Through her mesh artworks, Begum bridges diverse cultural and artistic traditions, crafting pieces that are both universal and deeply personal. They compel viewers to reconsider the intersection of materiality and light, offering a meditative experience that is as much about looking inward as it is about observing the external world. Her work stands as a testament to the transformative power of art in redefining space and perception.

I don’t force joyousness or positivity to come through my work, but I am naturally drawn to things that… illuminate.

Laura Finlay Smith, American Curator

Inspired by Lake Superior’s North Shore, George Morrison, who is widely regarded as one of the fathers of Native American modernism, scoured beaches on the East Coast and in Minnesota for the materials he used in his wood collage paintings. He referred to what he found as gifts yielded by the waters and collected the driftwood, drying it in his studio before beginning each work with a few pieces in the bottom left corner of the frame to begin the painstaking process of filling the entire frame.

The technique, inspired in part by the methods of his close friend sculptor Louise Nevelson, resulted in an abstract composition that called attention to the material properties of the wood, to the nuanced tones and textures, while a long, narrow sliver of wood along the top edge suggests a horizon line separating earth and sky. His work embodied the central role of the land in Native American identity.

Born into the Grand Portage Band of Chippewa in northern Minnesota, Morrison was born in Chippewa City in 1919, in a house near the shore of Lake Superior. He was sent to a boarding school in Wisconsin, attended and graduated from the Minneapolis School of Art, and in 1944, moved to New York and the Art Students League, where he made and showed work alongside modernist artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and Franz Kline.

As a Fulbright scholar, he studied and worked in Paris and Aix-en-Provence in 1952 and 1953, producing abstract art that synthesized expressionism, cubism, and surrealism. After teaching at the Rhode Island School of Design from 1963 to 1970, Morrison taught studio art and American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota, and from 1970 to 1982, he taught art and American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota, Cornell University, and Pennsylvania State University.

I always see the horizon as the edge of the world. And then you go beyond that, and then you see the phenomenon of the sky and that goes beyond also, so therefore I always imagine, in a certain surrealist world, that I am there, that I would like to imagine for myself that it is real.

Designed by Sarah Greenwood.